2025 Energy Predictions: Narrative Edition

American Mercantilism, American Idiots

Last week, I made some bets on the 2025 energy map for fun and accountability. But those bets were quantitative in structure, justification, and evaluation—and I’m fundamentally a qualitative analyst, a wannabe English major who took up engineering for career purposes.

American energy policy in the near future will, naturally, be determined by how the second Trump Administration responds to (and provokes) global events. We can make okay guesses about that globe, but nine years after that gold-plated escalator, we have a better read on Trump himself—provided we leave our partisan hero worship or derangement to the side.

I see an upside risk, and a downside risk. Let’s start with the former.

American Mercantilism

Trump’s initial campaign speech, translated into wonk speak, asks why the United States is still paying for globalization.1 He, and the irregular intellectual corps we call Trumpism, asked the right question. The United States does pay dearly for globalization: the American military functions as a global police force, the United States has run a trade deficit since the ‘70s, the US Dollar’s reserve status limits the Federal Reserve’s options, and the United States functions as an immigration haven for the rest of the world (at least mythologically).

To Trump, the problem here is deindustrialization and excess immigration, and the answer is “America First.”

To Trumpism, the issue is return on investment as a global power: if the US was going to invade Iraq, we should have kept the oil. “America First” isn’t necessarily autarky—it could be mercantilism.

Put your partisan feelings to the side: he’s on to something.

The recent bids for Panama and Greenland are examples du jour,2 but consider the Trump Administration’s 2019 trade deal with Japan—they ditched the Trans-Pacific Partnership and renegotiated a deal that kept a U.S. tariff on Japanese-manufactured automobiles but opened access for American agricultural goods in Japanese markets. You can say the U.S. didn’t get much out of the deal—but Japan arguably got less.

The goal of “America First” isn’t some juche 주체 closed-door foreign policy. Americans like going abroad, so long as the shops speak English and take Mastercard. Instead, imagine the Elizabethan imperial trade model, as framed in Philip Wilhelm von Hörnigk’s 1684 book Austria Over All, If Only She’d Do So3. The brief: devote as much land as possible to agriculture, mining, and manufacturing; cut your imports to the bare minimum of raw commodities; keep all your currency at home; export nothing but finished foods; and trade those exports for gold and silver alone. Screw everyone else.

Shale production makes this possible with energy.

Until 2015, the United States banned the export of crude oil. Congress only reversed this ban because of the boom in light, sweet shale oil begging for international markets. The United States has not only become a net exporter of crude oil and natural gas, but also a rising player in petrochemicals.

This has enabled more local manufacturing because of relatively low energy and feedstock costs. But it also gives the United States a strategic trump card—a high global oil price now helps American interests. Imagine: Congress reinstates an oil and gas export ban, strong-arms Canada into continued sale of the heavy, sour oil American refiners like, and authorizes a blockade on the Strait of Hormuz. The global price of oil spikes to $200/bbl4, liquified natural gas to $45/MMBTU5—except in the United States, where the price of energy falls. Panic breaks out. Iran’s economy seizes. China faces brownouts. And the United States gets to pick winners and losers with targeted energy sales and the only cheap finished goods left in the world. The global stage could turn into an American protection racket.

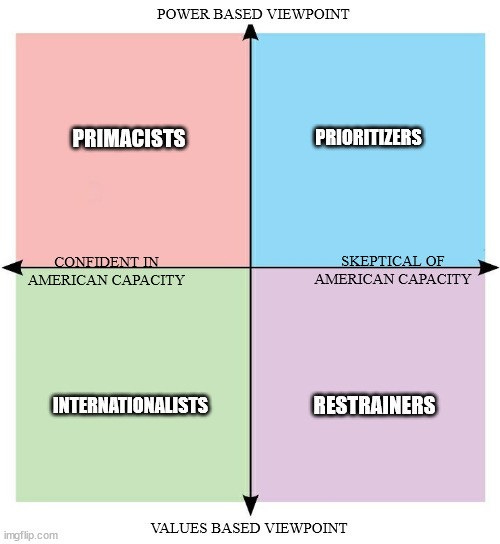

The United States might not go this far. As T. Greer describes in an excellent ChinaTalk article, there’s a political compass of foreign policy ideas floating in the Trump camp, based on 1) how confident you are that the United States could stomp our rivals and 2) whether we should fight for democracy or for naked power.

In Greer’s model, a “primacist” would be most willing to weaponize fossil fuel flows, but only an “internationalist” would care about what $200 oil does to European or Asian allies. Regardless, renewables are on the wrong side of the Sino-American trade war. That problem is fixable over a ten-year timeframe, but the messaging must change first. Politicians that want to win cannot frame solar, wind, and energy storage as climate action. However, they can frame them as jobs for blue-collar Americans, cash from export markets, and unburnt fuel that can be put to other uses.

Best case scenario, we see a glorious resurgence in American power.

American Idiots

Worst case scenario, we get an Armando Iannucci film.

Again, put your partisan feelings to the side: Trump isn’t hiring the A-team.

Several of his Cabinet picks are clowns. Congress isn’t necessarily on his side. His election campaign fell off the rails, yet he made his campaign manager chief of staff anyway. Not all his staff picks are rubes, but Trump has a habit of collecting grifters, also-rans, foreign assets, and the willfully corrupt into his orbit.

This hiring practice is a reaction against an amorphous cohort of “people in charge.” There are a lot of names for this cohort (some of them quite unsavory), but I like George Friedman’s term: technocracy. That is, the belief that only an expert can deal with the problem, because half the problem is seeing the problem. Notionally, I get the idea: if these DC bureaucrats were so smart, why haven’t they solved the economy already? Better clear them out and hire people who actually like the President.

We’re familiar with the mistakes of experts. But the new Trump staff aren’t exempt from such blunders. Instead, they’re susceptible to that and more: corruption, infighting, turnover, leaks, vulgarity, partisanship, stupidity. Even if Donald Trump was a genius befitting a God-Emperor6, he cannot run the country alone, and there are too many freaks, fools, and screw-ups working for him. If and when staff wash out in varying depths of disgrace, the Trump Administration will likely pass over sober policy experts out of mutual partisan antagonism,7 in favor of yet-dumber aspirants to federal desks.

More so than the “adult”-monitored first term, the incoming Trump Administration is uniquely vulnerable to unforced errors at the strategic and operational level. The team might pull through despite itself, but even the best-case scenario will be rife with confusion, finger-pointing, and collateral damage.

The Tipping Point of the Saecular Cycle

The long and short of Trump 2.0 is that we’re at the tipping point of a new saecular cycle—as in a saeculum, as in 80-90ish years, as in enough time for almost everyone who personally remembers the founding of the world to die.8 The last great tipping point was the Second World War, which destroyed the old imperial era and replaced it with the Cold War and the liberal international order. And that order is approximately as old and tired as outgoing President Joe Biden.9

Trump’s second administration will attempt to renegotiate the American approach to our institutions at home and to the world outside. This is a big ask—we’ll need to retool the entire governmental apparatus, from leadership roles to frontline staff pipelines.10 Even if Trump’s team knocks things out the park, they’ll struggle with implementation because there literally are not enough experts in tariff policy, drone warfare, or big-stick diplomacy to fill out the middle ranks—and there won’t be until at least 2030.

It’ll be bumpy. But by 2028, the America First coalition will sketch out their media environment, talent pools, status hierarchies, and post-Trump leadership cohort. By 2030, a cogent opposition will do the same. And by 2032, we’ll have a good idea of the New Order of Things. The groundwork is already under construction.

My job is to read the trendlines towards this future so that I can bankroll my penchant for road bikes and boutique espresso.

I’m going to post on Energy Crystals every Monday at 7 AM Eastern Time through end-of-year 2025. Subscribe if you want to read along.

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of their current or previous employers or any elected officials. The author makes no recommendations toward any electric utility, regulatory body, or other organization. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, the author has not independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author assumes no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

Call it the Bretton Woods Order, call it Pax Americana

Greenland is not the worst idea. Denmark will give us mineral and security access if we ask, but we hadn’t even asked at scale until Trump started tweeting about it.

Oesterreich über alles, wann es nur will

Up from $70/bbl

Up from $12/MMBTU

And he is not

You may blame only half of this on liberal anti-Americanism. A “visionary” executive who runs his mouth, forgets what he’s working on, micromanages staff when he remembers again, and makes women on staff uncomfortable, motivates good people to leave. I would know—I had an old boss like this.

I’m going off Strauss and Howe’s generational model. Peter Turchin has a similar idea of secular cycles, but the timelines seem slightly different in Turchin’s account.

This is the promise of DOGE—and like government efficiency activist Jennifer Pahlka, I am breaking out the popcorn with cautious optimism: