BONUS: Oil Prices, Explained

A brief explainer on buying, refining, and tracking crude oil

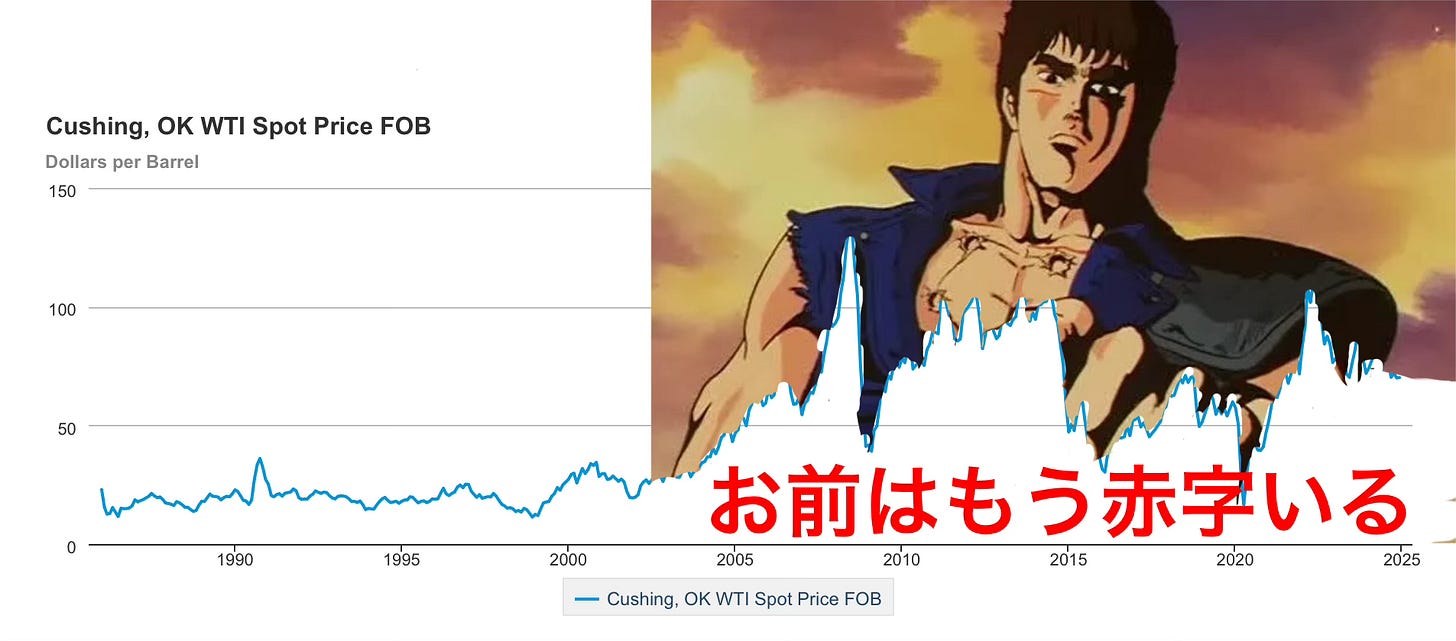

In my 2025 Energy Predictions post, I made a bet that the spot price of WTI crude oil would not fall below $65 per barrel ($/bbl) in 2025. But crucially, I specified a type of crude oil within a specific contract—I couldn’t simply say “the price of oil.” There isn’t a single price of oil, because there isn’t a single kind of oil.

Follow me down this rabbit hole, and I’ll explain why the Keystone XL pipeline was a big deal.

This is a BONUS post, produced at the recommendation of the renegades at the Defense Analyses Research Corporation. Follow DARC on X at @DefenseAnalyses.

Grades of Crude Oil

The most important thing to remember is that there is no one kind of oil—depending on where you get the oil (and how you get it), you’ll get a different mix of hydrocarbons and impurities you’ll need to clean out. Each barrel has a slightly different mix of goop, and thus each is worth different sums of cash. However, to facilitate trading oil at scale, industrial players have agreed on different grades of crude oil that are standardized for sale.

Brent crude oil is the global baseline. It originally referred to a type of oil extracted from the North Sea’s Brent oil field, but that field is dead. Now, Brent crude is a specified blend of oil from 5-6 different oil fields. You can’t buy a literal barrel of Brent blended crude oil—it’s a financial abstraction. Instead, you buy crude oil from a specific oil field (or group of oil fields), like Arab Light crude oil from the Ghawar Oil Field, at a basis price relative to Brent—say, Brent + 1.5 USD.

Crude grades run a spectrum of financialization, from field-specific grades tied to a specific vertical (like Ekofisk), to blended crudes that you can buy as a blend (like Dubai), to the complete abstraction that is Brent. Each crude grade is tied to a point-of-sale terminal, where you can buy oil now (at the spot price)1 or in the future (as a futures contract).2

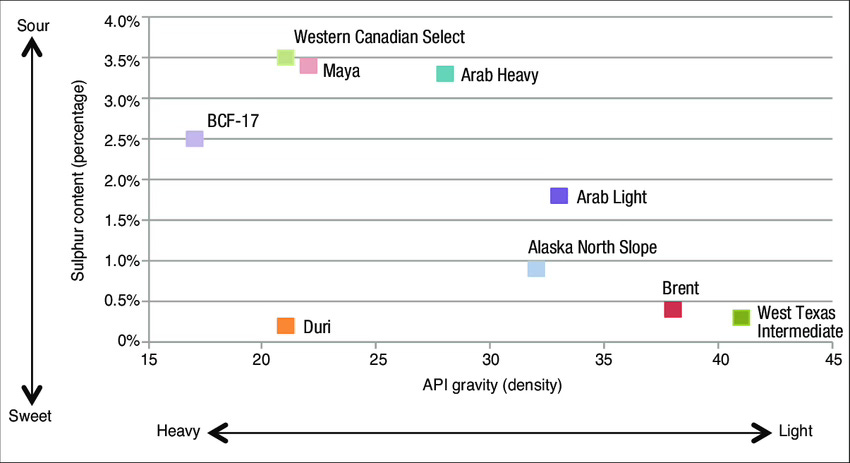

The “Political Compass” of Oil Chemistry

Different crude grades cost different amounts because they each have specific chemistries. Let’s use Bakken shale crude as an example. ExxonMobil has a handy-dandy assay report detailing the chemical properties of this North Dakotan crude grade. ExxonMobil cares about how much paraffin and naphthene they can get and how much vapor pressure they need to manage. But you and I only care about two factors: API gravity (in degrees, usually between 10° and 45°) and sulfur content (in percentage by weight, usually between 0.4% and 5%). The API gravity of an oil tracks its density—high API gravity means light oil; low API gravity means heavy oil. The API gravity roughly tracks the specific hydrocarbons you’ll get out of a crude: refiners may prefer lighter or heavier crude depending on what refined products they want. The sulfur, meanwhile, is mostly crud—sweet low-sulfur oil is easier to work with than sour high-sulfur oil. However, if you’re willing to scrub the crud out, then you can buy sour crude at a discount relative to other grades.

Within this two-by-two axis, you can build a “political compass” of oil chemistry: light vs. heavy, sweet vs. sour.

Note a few points on this chart: Up top, you’ll see Western Canadian Select (WCS), Maya, and Arab Heavy. WCS comes from Albertan oil sands. Maya comes from Mexico. Arab Heavy is primarily Saudi. These are all heavy and sour crude grades that American refiners like. On the bottom right, you’ll see West Texas Intermediate (WTI). That’s a blend of light and sweet American shale crudes, including the Bakken crude we just looked at. Some overachievers may have noticed something about WTI. Hold onto that thought while we talk about refineries.

Refining: The Worst Business to Be In

Commodity business suck because your prices are out of your control. If your business sells a commodity, your revenue depends on a twitchy market that you have limited control over—the best you can do is manage your costs appropriately. If your business buys a commodity, your costs depend on some twitchy market—and all you can do is ensure a buffer in your profit margin. A petroleum refinery must buy a commodity (crude oil, natural gas) and refine it into a different commodity (fuels, distillates, etc.), which means they cannot control their costs or their revenues. It’s a bad time!

You can track a refinery’s misery with the 3:2:1 crack spread: the price differential between three barrels of crude oil and the sum of two barrels of gasoline and one barrel of distillate fuel.3 The gas and distillate combo is a first-pass estimate of a refinery’s revenue-per-barrel. The crude oil is a first-pass of its cost-of-goods-sold (COGS).

A normal 3:2:1 crack spread is $10-30 per barrel. Compare that to a crude oil price of $70-90 per barrel. Then remember to add the cost of staffing, equipment, catalysts, depreciation, and so on. Then remember that a refinery needs tens to hundreds of millions in capex to build. Then remember how much permitting you would need before you break ground.

Petroleum refineries have no margin. Their free cash flow is a source of terror. The last American refinery with output beyond 200,000 barrels per calendar day started up in 1977, because this business model is terrifying. And remember that no two crude grades are the same. If a refinery had to change their supplier, it would have to retool its entire operation with its preciously slim capital supply.

The Keystone Pipeline, Explained

In the bad old days before shale, American refineries, especially around the Gulf of Mexico, typically relied on heavy and sour crude—Mexican Maya and Arab Heavy as defaults, extra-heavy and extra-sour Venezuelan crude when they could source it. By my best understanding, refineries did this because they could—because the heavier and more sour crude is harder to refine, it’s cheaper on the open market if you can source the technology and talent at home. Luckily, Texas A&M is right there.

Shale is a big change for these refineries. They are slowly retooling for the new crude, but it’s difficult and expensive. And there’s an easier approach, courtesy Alberta. Oil sands crude is, on the broad strokes, chemically similar to maritime Mexican and Gulf oil. Except instead of dealing with the perpetually mismanaged Mexican state oil company or the powder-keg Persian Gulf, you can work with friendly Canadians who don’t have the option to sell to anyone else.4

This is what the Keystone pipeline does—it brings heavy and sour crude oil from Alberta (where it’s extracted) to American refineries that would otherwise take maritime oil from Mexico, the Persian Gulf, or Venezuela. It’s not my job to determine whether the projected economic benefits of the Keystone XL pipeline expansion would have outweighed the projected environmental costs. That decision is based on values, and it was made ten years ago. But the stakes only make sense if you remember that Albertan crude and shale crude are not interchangeable.

So Why Are Oil Markets on Fire?

Oil hits that magic combination of complex chemistry, complex logistics, complex financial tools, complex politics, and universal applicability. Whether you need crude oil for materials, for fuel, or for foreign currency, you can’t go without. This makes demand in oil markets inelastic: if you need ten gallons of gasoline, you can’t get away with nine. You might adjust after a year (by buying a Prius, or switching suppliers), but right now you’ll pay whatever it takes. If a million barrels of oil per day went offline tomorrow, we’d see an immediate 5-15% spike in the price of oil. That is, losing just 1% of global crude supply would increase your gasoline bill by $5 per tank within days.

It takes 3-5 years to spin up a conventional oil play—5-10 years for offshore. But the price of oil changes on a whim. And how do you model oil demand over the twenty-year timeline you’ll run the asset? Do you take stated climate commitments seriously, like the IEA does? Do you scoff at “peak oil,” like OPEC does? Do you account for deglobalization and demographic collapse, like Peter Zeihan does? Do you model what would happen once NATO starts blockading Russian oil?

If you’re a buyer, you can hedge your bet with an oil future—you can set a call so that you’ll pay no more than $75 for oil, or a put so that you’ll sell at no less than $95. But who’ll agree to be a counterparty for those prices? Forecasting is always a quixotic affair—but forecasting oil supply in six months, oil demand in five years, oil prices anytime in between, has become even more impossible in the 2020s.

And yet you must make a bet. Otherwise, that tanker sails to another port.

Thanks for reading this explainer. I think the Tech Right / Abundance Left / Progress Studies cohort would benefit from learning the devil-harboring details of energy, and I’m happy to be that resource. Please share this run-down with your wonk colleagues, and remember to index with WTI, not Brent.

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of their current or previous employers or any elected officials. The author makes no recommendations toward any electric utility, regulatory body, or other organization. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, the author has not independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author assumes no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

“Now” means different things to different markets. For crude oil loaded onto a ship, that means next month. For Bakken pipeline crude, that means tomorrow. For electricity in New England, that means within the next five minutes. The difference comes down to the speed of transport, from supertankers topping out at 16 knots to wires carrying electricity near-instantaneously.

This is also why my prediction on oil prices was based on the Cushing, OK terminal. Oil at Cushing is a domestic price index, and it costs a different amount relative to the same oil grade exported from Houston, TX.

This triples your index problem—each crack spread tracks a different crude grade, a different gasoline grade, and a different distillate product.

Somehow, despite getting the short end of this stick, the Prairie provinces are still the core engine of growth in Canada. What’s going on, Ottawa?