The Facts on American LNG Exports Have Been Settled

The DOE LNG report doesn’t substantively disagree with the best report “countering” it.

On 17 December 2024, the Biden Administration’s Department of Energy, headed by governor-turned-energy-wonk Jennifer Granholm, released a report on American liquified natural gas (LNG) exports so controversial that people lost their minds over the findings before they were even released. The result, having read the report, are only shocking if you don’t consider the context underlying those numbers. Granholm et al. simply don’t provide that context, because they have an axe to grind in anticipation of Trump 2.0.

I’ll provide that context for you, starting with a “competing” economic report published to Standard & Poor’s (of the 500) by a team led by estimable energy mapper Daniel Yergin.

The topline findings from Yergin et al. are:

LNG exports, and the shale natural gas drilling that supplies it, have contributed half a billion dollars to the United States GDP between 2016 and 2024. This is about 1.6% of 2024ish American GDP, spread over seven or eight years. This is serious scratch, but not a deciding factor on whether there’s a recession.

The United States is now the single largest global supplier of LNG. A key benefit of American LNG is that it can be sold while the boat is already moving, allowing for flexibility in where the weight goes. Most of that LNG goes to Europe and Asia, making the United States a valuable trade partner for countries like Japan, South Korea…and China, who would grow as a customer of American LNG.

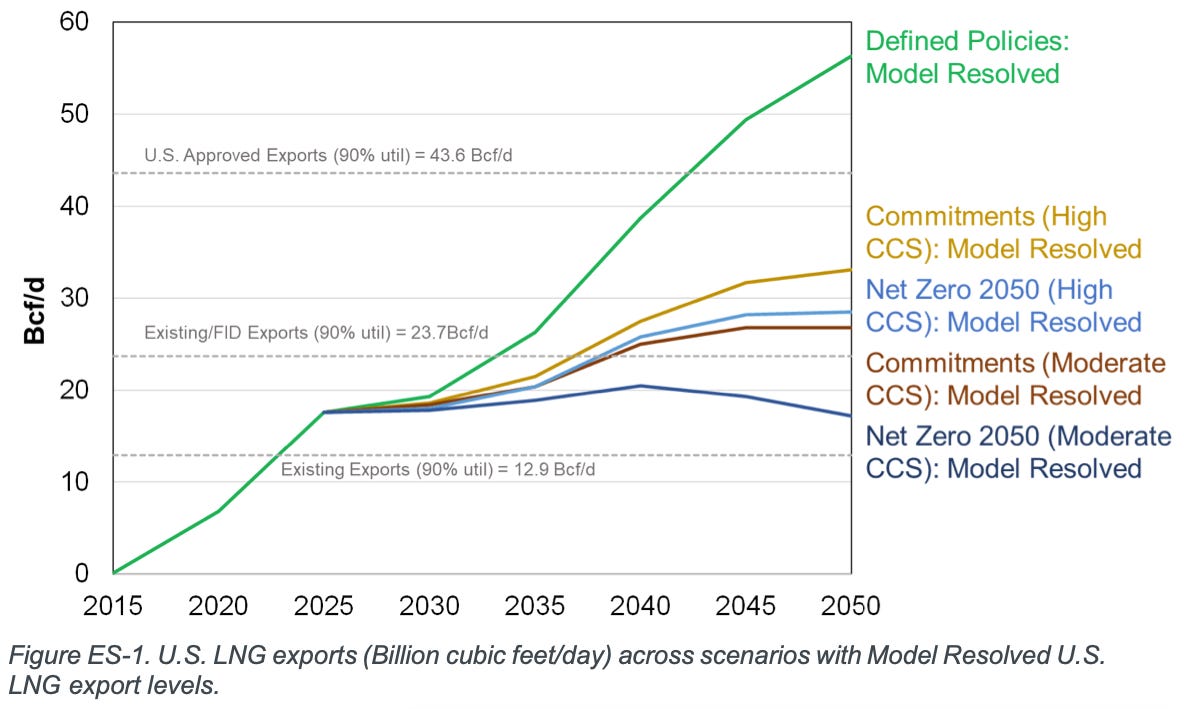

The United States will continue to export a lot of LNG with existing export terminals and currently-under-construction export terminals. However, there’s currently a “pause” on approving construction for additional terminals. Let’s call this the “Baseline Exports” case.

However, if DOE ditches its “pause” and approves construction for more LNG export terminals, the United States will export a metric butt-ton of LNG. Let’s call this the “Unconstrained Exports” case.1

The extra LNG exports in the Unconstrained Exports case will add $1.3T to the American GDP between 2024ish and 2040, relative to the Baseline Exports case.

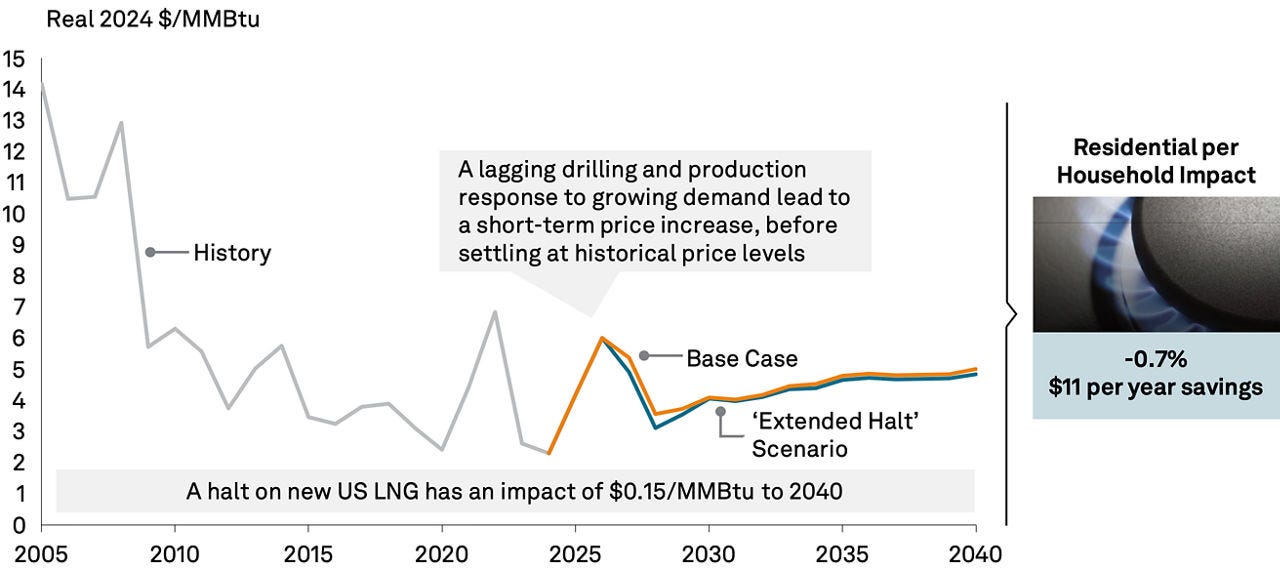

The feared increase in domestic natural gas prices in the Unconstrained Exports case is unwarranted. Because marine LNG prices are an order of magnitude more expensive than domestic pipeline natural gas, many (including I) feared that extra export capacity will suck up domestic gas supply that otherwise would go to domestic customers.

In both cases, the Henry Hub wholesale gas price would settle around 4.50-5.00 $2024/MMBTU in 2040, with the Unconstrained Exports price being marginally higher.

In 2040, residential gas prices would be less than 1% more expensive in the Unconstrained Exports case versus the Baseline Exports case.

The LNG not produced in the Baseline Exports case versus the Unconstrained Exports case would be replaced by 1) other LNG sources, 2) other fossil fuels, in particular coal and oil, and 3) a little bit of renewable energy. Yergin et al. promise a more detailed analysis of climate impacts, but eyeballing their estimates suggests that the emissions impact of the two cases come out to a wash.

The overall takeaway for Yergin and his team is, “Look, the costs of unconstrained LNG exports are pretty marginal, so why leave all this cash on the table?”

This assessment seems reasonable. I personally didn’t dig into their model, because I’m a qualitative analyst. To me, analyzing spreadsheets is hard, and it’s annoying, and I won’t do it for free. If you want me to do hard things, leave a comment saying it would be worth your money.

What matters to me is the quality and incentives of the team. Daniel Yergin himself is a uniquely competent energy analyst, because he can explain energy economies as they are today (and not 20 years ago) without stinking of a bridge he’s trying to sell.2 I trust him to call balls and strikes effectively. However, he and his team are getting paid by a financial analysis conglomerate. The report started with an advocacy position (“line go up is good”) and built an economic model to back it up.

What matters to me is that Granholm’s team at DOE broadly agrees on the topline impacts, despite advocating the opposite policy position.

Getting Back to Granholm

Which brings us to the Granholm report. The core assumption of this report is that we cannot actually know what 2050 global LNG demand will look like. On one hand, LNG has proven a valuable energy source: expensive, sure, but good deal more stable than alternatives like pipeline (Russian) gas or intermittent renewables. On the other hand, multiple rich countries have made decarbonization targets that necessarily target LNG demand, with varying levels of confidence that they’ll do it.3 This is the same core issue underpinning the “peak oil” debate between the IEA and OPEC: how seriously do you take climate promises? Granholm et al. take a side on this debate, claiming that there’s already enough export capacity to fulfill forward projections of global LNG demand. Which…might be the case.

They make other findings that seem to key off a similar idea of Baseline vs. Unconstrained Exports,4 but they’re tempered by estimates of global LNG demand dependent on how closely the world keeps its climate promises:

The United States is now the single largest global supplier of LNG. A key benefit of American LNG is that it can be sold while the boat is already moving, allowing for flexibility in where the LNG goes. Most of that LNG goes to Europe and Asia, making the United States a valuable trade partner for countries like Japan, South Korea, and China. Granholm et al. and Yergin et al. agree on these core facts.

The United States will continue to export a lot of LNG with existing export terminals and currently-under-construction export terminals. Granholm et al. argue that unless the world collectively breaks its climate promises at scale, Baseline Export capacity will be enough for global demand.

The extra LNG exports in the Unconstrained Exports case will add $900B to “gross industrial output” between 2024ish and 2050, relative to the Baseline Exports case.

In the Unconstrained Exports case, the Henry Hub wholesale gas price would settle around 4.62 $2022/MMBTU in 2050, which trends lower than the Yergin et al. estimate.

In 2050, residential gas prices would be 4%5 more expensive in the Unconstrained Exports case versus the Baseline Exports case, which is not that different from the Yergin et al. estimate.

Those increased residential energy prices would look like an extra $50-125/year, or $4-10/month. Seasonal fluctuations dwarf this projected price delta.

The LNG not produced in the Baseline Exports case versus the Unconstrained Exports case would be replaced by coal and intermittent renewables in particular. Again, qualitative agreement with Yergin et al., with likely quibbles on the balance of coal and renewables replacing LNG.

The extra LNG exports in the Unconstrained Exports case will increase global cumulative greenhouse gas emissions by 0.002-0.05% between 2020 and 2050, relative to the Baseline Exports case. This will return a cumulative social cost of carbon (at a 2.5% discount rate) between $3B and $170B over thirty years. By comparison, NVIDIA’s FY2024 revenue was $61B over one year.

The increase in LNG exports will lead to miscellaneous environmental justice problems, because industrial plant is always sited next to where the poor people live, because siting industrial plant within view of rich people’s houses is an easy way to get shot in permitting hearings.6

The overall takeaway for Granholm and her team is, “Look, the financial costs of constraining LNG exports are pretty marginal, but so why pay all these environmental costs?” Granholm is more obviously partisan than Yergin, but she’s not stupidly partisan. The underlying numbers pass a sniff check, even if the headline doesn’t.

But They’re Making the Same Points

Look at the narrative overlap between these articles:

Removing LNG export constraints will add a trillion-ish to the GDP over 15-30 years. That’s serious but not critical dough.

Removing LNG export constraints will increase domestic gas costs over 15-30 years by an amount so small that we should ignore it.7

The climate impact between constrained and unconstrained LNG exports is a wash. The unsold LNG would be replaced by coal and renewables.

Both reports are operating off the same baseline facts: the United States produces a stupid quantity of natural gas, of which a mere fraction is chilled into LNG that still amounts to a market-leading export volume. We could continue freezing LNG export permits and remain the biggest fish in LNG export, matched only by allied Australia. We could also lift the restriction on new LNG export terminals and saturate the market even more.

These competing reports, with separate methodologies from separate ax-grinding operations, agree on many of the core facts and tradeoffs with respect to American LNG export infrastructure. The difference is in values. Do you value GDP growth and jobs? Do you value emissions reduction and local environmental costs? Or maybe you, like I, notice an increasingly sturdy noose around Beijing’s energy balance? That could be leverage, should Xi Jinping get any ideas.

What frustrates me is that it seems no one is talking about this. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) posted an “Experts React” listicle dithering over the points outlined in the above bullets, but none of them brought up that we have stumbled into cross-partisan consensus about the shape of American LNG export capacity.

The argument is over. We’re quibbling over values now.

When will people notice?

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of their current or previous employers or any elected officials. The author makes no recommendations toward any electric utility, regulatory body, or other organization. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, the author has not independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author assumes no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

The names for “Baseline Exports” and “Unconstrained Exports” are my own. Yergin et al. and Granholm et al. use their own terms and likely differ in their assumptions.

Compare Yergin’s The New Map (2020) to the Substack posts of Doomberg, Robert Bryce, and David Roberts. I’m cherrypicking articles that especially stink of partisanship, but Yergin never sinks this low. As a general rule, any energy analyst that thinks a given energy technology will either save the grid or break the grid is a partisan hack. Elon shills will tell you solar and storage will save the world. Environmentalists will tell you it’s solar, offshore wind, and distributed control software. Fossil fuel aficionados will tell you it’s small modular nuclear (SMR) and liquified natural gas (LNG). They’re all thinking too narrowly.

On a secret, third hand, do we really expect many of these countries to stay rich? I would put good odds on the United Kingdom (About Even 45-55%), Germany (Probable 55-80%) and China (About Even 45-55%, high variance in outcome) all seeing LNG demand fall because of economic decline because of aging and mismanagement.

Again, the names for “Baseline Exports” and “Unconstrained Exports” are my own.

In particular, a range between 3% and 7% depending on domestic gas supply.

Legend has it that saying “offshore wind” three times will summon a rich Nantucketer, who will crash their Range Rover into your living room babbling about “saving the whales.”

One of the most important lessons I learned in engineering school is that most deviance under 5% is not worth thinking about.