The Work Distribution Chart & Ex-Analyst Syndrome

Operational process is the point of middle management

Kevin Hawickhorst’s Substack State Capacitance is a treasure trove of historical management literature based on a core premise: The United States Government managed itself better in the 1940s than it does today. As a finer point:

Incredibly, politicians had better dashboards in the era of punch cards than we have in the era of AI. The decline in government competence runs deeper than our inability to match the speed and economy of New Deal construction: even their accounting was better.

The difference is in process—I don’t think bureaucrats of the ‘30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s were smarter, better-trained, or less-corrupt than modern bureaucrats, and they certainly had fewer tools at their disposal. Instead, Hawickhorst argues (convincingly) that staff were managed better.

Case in point: consider the Work Simplification program. This was a Bureau of Budget project starting in 1942, which turned into a consulting-style circuit of management-training workshops, complete with a handy-dandy pamphlet and a set of posters in an art style we now recognize as “the Fallout look.” If you ping Hawickhorst, he’ll email you a copy!

In this post, I want to apply one of the Work Simplification programs, the Work Distribution Chart, to a common problem I’ve seen in municipal electric utilities.

Operational Process, Briefly

One of my core lessons from my MBA program is the differentiation between strategic, operational, and tactical concerns. Strategic planning is the big-picture, 3-5-year, what-are-we-doing-and-why consideration that (should) occupy executives’ time. Tactical tasks are the ground-level, shop-talking, in-the-weeds analytical and hands-on work that ultimately are what an organization does. Operational process is in the middle—figuring out who does what, how things are tracked, and how bills and paychecks are fulfilled. Ultimately, operational excellence counteracts the entropic cruft and chaos that all organizations trend towards.

Middle managers are supposed to handle operational process. MBA programs are supposed to teach people how to do it. This is why I’m getting classes on reading (not writing) accounting and financial materials, building and managing teams, and talking about products to staff and customers alike. These operational skills are useful regardless of what your organization actually does.1 This blog, Energy Crystals Dot Eye Oh, primarily focuses on operational concerns, which is why I care so much about staffing, market design, and how much things cost.

The Work Simplification program is designed for these middle managers—or “first-line” supervisors, as the pamphlet calls them:

The “first-line” supervisor is the one man who is constantly face-to-face with the realities of running a government office. Most of the paperwork problems revolve around his desk. He knows both the work requirements and the problems first-hand. He does the job [of management]—and the one who does the job is the one who is in the best position to do the job better. [Emphasis original]

This does not describe my job as a utility energy analyst—this describes my boss’s job.

The Work Distribution Chart

The Work Distribution Chart is the first of three pieces to Work Simplification,2 answering the straightforward-but-prickly questions of:

What does your office unit do, actually?

Who in your office unit does what?

The pamphlet recommends managers follow the below steps:

The manager asks every staffer in the office unit (presumably a staff of 3-6, plus the manager) to write out their tasks, with an estimate of how many hours each task takes. This reverse-engineers everyone’s job descriptions.

Separately, the manager writes down a list of activities the office unit does. Each activity is a category of task. This reverse-engineers the responsibilities of the office unit—hopefully it reflects what the staffers say they do!

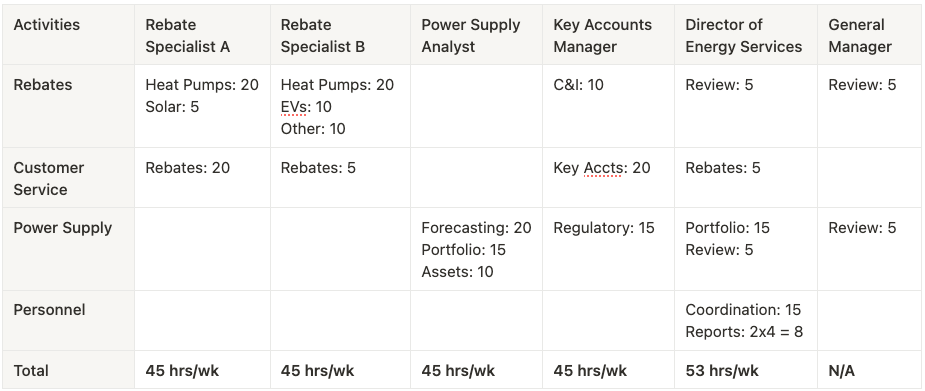

The manager combines these tasks into the Work Distribution Chart—the X axis corresponds to each employee, the Y axis corresponds to each activity, and each cell holds tasks and respective time expenditures.

Simple Enough, Right?

Of course not.

Let’s pull together an example based on an office unit that I’m familiar with: a municipal light plant’s energy services division. This is a catchall division that covers anything that isn’t customer service, finance, or engineering. Every utility handles it differently—some call it the integrated resources division instead—but an example office might include the following activities, measured in hours of time per week (hrs/wk).

Rebate Processing

Heat pump rebate processing: 40 hrs/wk

EV rebate processing: 10 hrs/wk

Solar rebate processing: 5 hrs/wk

Other residential rebate processing: 10 hrs/wk

Commercial & industrial (C&I) rebate processing: 10 hrs/wk

Rebates review: 10 hrs/wk

Customer Service

Key account management: 20 hrs/wk

Rebate customer service: 30 hrs/wk

Power Supply

Portfolio management: 30 hrs/wk

Supply & load forecasting: 20 hrs/wk

Power supply review: 10 hrs/wk

Grid asset management: 10 hrs/wk

Regulatory interface: 15 hrs/wk

Management

Personnel management: 2 hrs/wk per direct report

Inter-Division Coordination: 15 hrs/wk

If we split this out into a model office unit, we might get something like this:

Wait, Something’s Wrong Here

Based on this chart, the pamphlet recommends asking the following questions:

What activities take the most time?

Is there any misdirected effort?

Are special skills being put to use?

Are employees doing too many unrelated tasks?

Are tasks spread too thinly?

Is work distributed evenly?

These are good and important questions, but the example I gave above has other problems:

The Director Can’t Manage Anyone

The example work distribution chart suggests that almost everyone in the office is a little bit overloaded.3 But the Director of Energy Services is overloaded before they get to managing their four direct reports. This setup is a recipe for absentee management: fifteen-minute one-on-ones, double-booked meetings, emails lost in inboxes, year-end performance reviews in April.

The particular issue here is that the manager is doing analyst-level work—power supply portfolio management—as a manager. This might be because they’re the only one qualified to do it, or because they like the meetings and number-crunching, or simply because they’re too busy to hire and train up another analyst to make it happen, because…

There’s No Time for Process Improvement

Notice what isn’t on this task list: hiring, process improvement, new program ideas, documenting anything, all-hands meetings, staff training, staff onboarding. The team isn’t simply overloaded; they’re so overloaded that they don’t have the time to address the reasons why they are overloaded.

And while handling this quagmire, the team might get new projects from on-high. “Hey, we’re looking at implementing a distributed energy resource management system (DERMS), and how about a financing option for the heat pump rebate, and oh, is anyone keeping tabs on this Clean Heat Standard thing?”

Also, Why is the General Manager Involved?

I’ve heard that in one municipal electric utility, the General Manager reviews every rebate. In another, the Director of Finance does grant writing and reporting paperwork for federal grants. Every time a General Manager (or similar category of Principal or Director or C-suite) dips into tactical-level work, it’s automatically a problem. For one, the senior leadership should have better things to do. But more importantly, this dive to ground level steps on the toes of their direct reports: operational-scale middle managers.

I’ve frequently gotten requests direct from the “Boss’s Boss.” It routinely confuses the chain of command, because now I don’t know where the buck stops for a particular decision. Whose approval do I need? Who needs to be CC’d on this email? Should I be waiting for so-and-so’s approval, too? Will someone kill this idea from a thousand clicks at the last second?

Ex-Analyst Syndrome

The core challenge here is that pretty much every manager in the electric utility industry started out doing tactical work: former line engineers, former power supply analysts, and in some cases former consultants or political aides. A lot of the top leadership have MBAs, but what about the middle managers? I doubt many pick up training in how to manage a staff, much less how to operate a Work Distribution Chart.

And yes, this is a subset of the Peter Principle, but there’s more to Ex-Analyst Syndrome than mere incompetence. Out of the six managers I’ve had in my 4-6 years of work experience,4 all of them seemingly preferred to do my job instead of theirs. This meant annoying spurts of micromanagement, hoarding tasks instead of delegating them to ground staff, sitting on decisions for weeks, and most pressingly one-on-one check-ins in which my boss clearly needed to be elsewhere right now, so could you please make this conversation quick?

This is a recipe for sloppy management: understaffing, short-term thinking, prioritizing problems by urgency instead of importance, frontline staff turnover, and ultimately not getting things done. The strategic thinking is done out loud in front of the Board of Commissioners, the tactical work is done whenever and however by whomever, and no one thinks seriously about how to improve duplicative, poorly documented, hurry-up-and-wait processes.

And as dire as this problem is in the electric utility industry, this lack of effective management has even more dire implications for the United States Armed Forces, as “Tiger Boyd” describes for DARC.

This frustrates me, because effective management does not appear to be rocket science—pay attention to your staff, document where everything is, update that documentation quarterly, and maintain the guts to stand by decisions, eat downside risks, and let direct reports screw up on your watch.5 And sure, managers are busy; everyone is busy, but operational process and staff management are the job of management, not willfully taking up tasks that could have gone to the tactical staff you hired to, uh, do those specific tasks.

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of their current or previous employers or any elected officials. The author makes no recommendations toward any electric utility, regulatory body, or other organization. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, the author has not independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author assumes no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

Unfortunately, most middle managers are bad at operational process, and most MBA students think they’re strategists. This is in part why people think that middle managers don’t do anything and that MBA grads are rubes.

I wrote about another tool, Process Charts, here:

People in tech and consulting are looking at these hour counts like they’re rookie numbers. I work in the public sector. In this industry, there’s an expectation that you go home and see your family.

I’ve had great management in my career!

The screwing up is important, because—as Mr. Beast will attest—screwing up is part of the learning process. Of course, having the guts to stand by decisions, eat downside risks, and let direct reports screw up on your watch requires uncommonly high risk tolerance for 2025.

I'm very happy to have hit the point in my career to have a manager level position, with zero "reports to's"

I suspect managers in many organizations never receive training and don't know what to do! When you don't know what to do, you do what you know, which may be your prior job. Also, utilities (in my experience and other organizations for all I know) tend to 'promote' analysts they really like, rather than look for 'managers' from inside or outside. The HR metrics commonly don't reward managerial activity. Nor do state public utility regulators (or, in your case, a publicly elected board) recognize it as a valuable activity. What isn't deemed valuable, won't get included in an approved revenue requirement, public or IOU. Electric utilities, again public or private, are part of a system in which all of the participants expectations of what 'should' be, hold all the rest in place where they are. I have thought long and hard bout how a utility could break out of this, but have no ideas. If it happenes, however, it will start small and be perceived as incremental, I suspect.