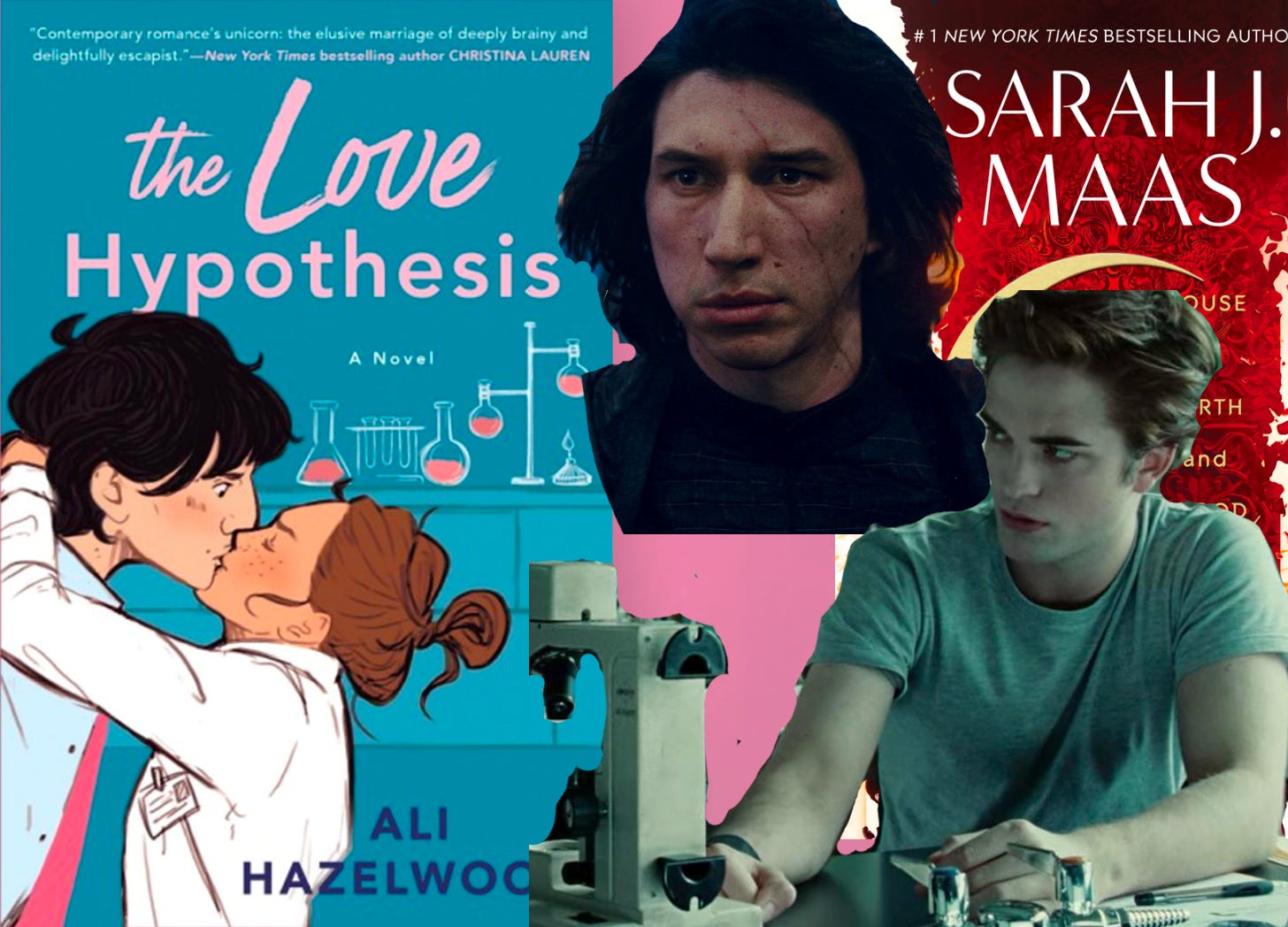

BONUS: The Love Hypothesis (2021) Dreams of Patriarchy

I tried to read fiction on my vacation.

A year ago, I started Sarah J. Maas’s House of Earth and Blood at the recommendation of my cousin. It’s pretty good.1 But the particular power fantasy of the book proved curious to me. Bryce Quinlan, doing her best Hiro Protagonist impression, barges through the narrative as a silver-tongued historian, an impressive marksman,2 a legendary party animal, an heiress of a Fae birthright, a slayer of god and monster alike, and…the hottest girl in Lunathion.

I was struck, particularly, by how many characters commented on Bryce’s body—most notably an archangel that Bryce eventually kills in a spectacular climactic sequence. The narration highlights not only Bryce’s fashion sense and quality of hair, but also her literal figure in a manner that calls to mind a male gaze…in a book written by a woman, for young women. That male gaze is ultimately situated within a love interest: Orion “Hunt” Alathar. Hunt is (to me) an unexpected addition to a teenage girl’s power fantasy—a brooding black-winged angel of death, a failed revolutionary condemned to wet work for the empire he sought to destroy, a dude-bro who plays video games and watches baseball sunball in a cap and sweatpants, and ultimately a savior of his fair damsel in distress. Bryce Quinlan saves the city, yes, but only after Hunt nearly dies to protect her. The hot, protective boyfriend is part of the power fantasy, too.

Getting Intimate for the Bit

Ali Hazelwood’s 2021 The Love Hypothesis centers Olive Smith, who is best characterized as “Bella Swan in Stanford.” The text repeatedly insists that Olive deserves to be in her Stanford Ph.D program—her research is impressive, and her motivations are noble. But that text also implies that she’s barely hanging on: she’s broke, disheveled, impulsive, and victimized by tight funding, poor equipment, and awful classmates (with the specific exception of her two friends). This seems to be the equilibrium for a strong-yet-relatable female protagonist: if she surpasses her challenges by more than the skin of her teeth, she’d no longer be relatable, but if she succumbs or is diminished, she’d no longer be aspirational.

Deliberately contrived plot circumstances put her in contact with male lead Adam Carlsen, a professor in her department described as brilliant, impossibly successful, and prickly to an exaggerated degree. Olive suggests “fake-dating” Adam for a month, which he assents to for his own reasons. From there, the plot runs through a variety of rom-com plot contrivances, from “not enough space in the auditorium” to “too much sunscreen in her hands” to “he took the last bag of the snack she likes and now has to share.” These contrivances serve to shower Olive in minor intimacies—sitting in a man’s lap, imposing a chamomile tea on him, luxuriating in his smell, mooching from his food—without the indignity of asking.

Oddly, Hazelwood seems to misunderstand the motivations and characterization of her own male lead. The narration describes Adam as imperious and callous, a man who “obviously [considers] empathy a bug and not a feature of humanity,” but he acts with an empathetic understanding verging on telepathy. He picks up on the fake-boyfriend ruse with one encounter and one eavesdropped conversation, and he immediately plays along without prompting. Whereas a realistically boorish man has neither knowledge of others’ minds nor interest in learning, Adam knows exactly what’s going on. He simply chooses not to be polite. In fact, he gets a kick out of unnerving people, and he learns that juxtaposing his infamous demeanor with an eminently normal fake-girlfriend is an incredible prank on the whole department. Adam gives Olive a mercenary reason for playing fake-boyfriend, but his dialogue suggests he is trying his damndest not to laugh.3 And why wouldn’t he? This fabricated romance is an extended comedy routine with someone who is (presumably, but never confirmed to be) pleasant on the eyes. And the longer it goes, the funnier it gets.

The Straight Man in the Narrative

My Brother, My Brother, and Me (MBMBaM, pronounced /məˈbɪmˌbæm/) is an improv comedy podcast hosted by (in descending order of age) Justin, Travis, and Griffin McElroy. After fifteen years of production, the trio have proven masters of the craft, as seen in the vignette of Cursing Jerry and Origami Steve. Justin, as Origami Steve, plays the straight man, holding a calm demeanor through the bit as Griffin (playing Cursing Jerry) and Travis (playing a teacher) gesticulate at each other about Origami Steve’s eponymous talents. But ultimately, the straight man holds the final punchline: as the teacher (after much interruption from Cursing Jerry) asks if Origami Steve can fold books into words, Origami Steve proclaims, “Only Bibles!”

This final line elevates this vignette from a funny scene in a podcast to a Bit For the Ages immortalized by a fan animation with more than one million views. And it rests on a comedic straight man pulling his punch for as long as the narrative can stand. Although Justin says the least in this scene, it’s his bit. He controls the narrative, he sets the tempo, and he delivers the punchline that brings the house down.

Adam Carlsen, similarly, plays the straight man in The Love Hypothesis. He maintains the same deadpan delivery for science talk, genuine advice, and flirting, most notably with an extended running gag about collating the fake-dating scenarios into an increasingly-dense Title IX complaint. Like Justin McElroy, Adam controls the narrative, sets the tempo, and delivers the punchline of Olive falling in love despite herself.

I couldn’t finish the story. The banter, no matter how cute, was outside my taste. By Chapter 11, I had gotten the information I asked for.

Many Feminists Still Yearn for Patriarchs

Olive, despite her tragic past in a foster care system, is in my proverbial league—mid-twenties, educated, building a promising career but not quite there yet. If I lived in the Bay Area, Olive would have swiped left on my Hinge profile. But instead, she falls for man who is so brilliant, so awash in prestige and grant funding, that the administration worries he’s too good for Stanford. I’ll set aside his (literal) movie star looks—The Love Hypothesis is a power fantasy, too—but I rankle at the expectation that, however empowered Olive may be, she deserves a boyfriend who is yet more than her. This is by no means the historically anomalous “trad wife” ideal of the postwar United States, but it is not equality, either.

This is frustrating to me, because I spent my college years among feminist activists, seriously seeking a model of masculinity based on peace, equality, and mutual respect. And yet Hunt Alathar and Adam Carlsen (and their progenitor figure Edward Cullen) suggest that many purportedly feminist women really do yearn for a demigod hunk to capture their awe and deliver them from threat. That’s a patriarchal expectation! These self-proclaimed feminists want not to smash the patriarchy but to dilute it. Although neither Bryce Quinlan nor Olive Smith ask their boyfriends to foot their bills or give them babies, both books—for all their fanfare about empowered female characters—still cast aloof, physically imposing, and hyper-competent men as the sexy deuteragonist.

What should I, a man sympathetic to the feminist project, make of this? I can re-read bell hooks’s The Will to Change (2004), but hooks does not offer nor claim to offer a complete program for Male Feminism. And I see limited evidence that a fully-integrated soul embedded in a loving community (as hooks recommends) is sexy—unless the man first captures awe and delivers from threat. By contrast, David Buss’s The Evolution of Desire (1994) suggests that women’s desires for status, ambition, intelligence, strength, kindness, and commitment have biological underpinnings. There is evolutionary selection pressure towards men who can capture a mate’s awe and deliver her from threat, and Buss implies that fighting that pressure is counterproductive. But a corollary of that conclusion is that eradicating toxic masculinity is a misleading goal: the reckless self-destructiveness, stoic machismo, and violent tendencies described as toxic masculinity are the immature precursors of the dogged ambition, emotional stability, and protective strength that these romance novels tell me are desired.

What Is Asked of the Men?

And what of the men’s needs? These fantasy boyfriends are shown to accommodate and mirror the protagonists’ emotions, but they are not shown to tremble, to embarrass, to succumb, to seek deliverances of their own. Neither Hunt Alathar nor Adam Carlsen nor Edward Cullen burden their love interests. None of them are made low and pathetic. Yet I am low and pathetic, some of the time!4 Where, in these Bechdel-Test-passing, protagonist-empowering, patriarchy-smashing, by-women-for-women, romantic power fantasies, is the room for my liberation? What if I seek deliverance, too?

Instead, I take away the unfortunate prescription to deliver the romantic fantasy, costs be damned. I am to earn a sumptuous salary, and look unimpeachably gorgeous, and heal my wounded spirit, and impress all her friends, and assume benevolent leadership, and maintain a positive ledger on household chores, and intuitively empathize with her problems, and maintain my responsibilities to my Purpose because I have other things to do besides fall in love—and all this without burdening the poor soul I beg to love me.

At my current pace of growth, I could procure the total fantasy by my mid-thirties. I may even manage to hide its difficulty. But that fantasy is no feminism. Ali Hazelwood and the readers identifying with Olive Smith are asking for a patriarch.

So much for liberation.

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only.The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of their current or previous employers or any elected officials. The author makes no recommendations toward any electric utility, regulatory body, or other organization. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, the author has not independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author assumes no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

I made it about halfway through House of Sky and Breath. Like the Hunger Games trilogy, the Crescent City series falls off quite quickly, and my cousin reported that the third book was so bad it ruined the prior two books for her.

Entertainingly, Maas’s writing reveals she has no idea how guns works.

Relaying the story’s background as a Reylo (Rey & Kylo Ren from the Star Wars sequel series) fan fiction distracts from the narrative. Of the core cast, only Adam reflects his Star Wars counterpart, insofar as he reads like Adam Driver reprising his role as Kylo Ren for an SNL parody.

Even admitting as much is low and pathetic!