The Strategic Futures of Electric Utilities

The diverging futures of the electric grid

One rule I hold myself to on Energy Crystals is that I don’t have a strategic vision on where the grid should go. This is partially because my sympathies are divided, and partially because strategy not my job: I’m an analyst, not an ideologue. My job is to explain, not to convince.

Unfortunately, I am apparently more able to articulate the ideological futures of electricity than the ideologues. And if they can’t name their arguments, I must do so instead. I will work off an adaptation of that oft-memed ternary soil chart, based on the three core priorities of an electric grid: reliability, low cost, and decarbonization. Ternary charts are counterintuitive to read, so I recommend starting with this explainer video so that you can follow the chart:

With that rundown, here’s my soil chart.

This is a long post by my standards—there’s more to it than could fit in the email version of this post. I recommend reading it in stages.

The Conventional Grid: Defining “Keep the Lights On”

Balancing reliability and low cost, with limited decarbonization.

In 2025, “the lights” are LEDs. Their net energy cost is negligible. But electricity now underpins far more than lights—it’s air conditioning, refrigerators, internet, the pumps and motors in furnaces and boilers, industrial processes, and compute. The longer you go without it, the more of your life reverts to the 18th century. And yet, “keeping the lights on” is more complicated than a simple edict. There are three metrics, and in conventional electric grids, they’re ordered by priority.

1. Reliability

By reliability, I mean the degree to which you can use electricity without thinking about it. Any time you’re reminded of the material reality of the grid is a reliability failure. It’s power outages, yes, but it’s also flickering lights, tripped breakers, public safety power shutoffs, complexity in your electric bill, and mental effort spent on your electricity use. You should not need to think about your electric utility. Every customer call, every Facebook Mom’s Group post, every lay conversation about electricity, is a failure of a utility’s duty to facilitate your life without wasting your time, raising your blood pressure, or making you feel stupid.

2. Low Cost

Low cost is more straightforward: it’s the amount you pay for electricity, whether that’s on your electric bill or on equipment like solar panels, vehicle-to-grid (V2G) equipment, backup generators, or battery energy storage systems like the Tesla PowerWall.

Every utility engineer dreams of perfect reliability: fully undergrounded wires, redundant substations, backup generation for our backup generation, and the extermination of every squirrel in our service territory. But there are diminishing returns on grid robustness, and if you’re, say, a rural electric co-op with under ten customers per mile of wire, you can’t simply double everyone’s bill to bulletproof your system.

Reliability is the ultimate priority, but it’s not the only priority.

3. Decarbonization

Electric utilities primarily track decarbonization through records of their purchased power. In New England, these look like Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) collected per MWh and compared against our total sales, somewhat independent of when these RECs were generated relative to our actual electric sales. We can buy and sell these RECs independent of our power supply. If this arrangement disgusts you, remember:

Once the electrons are in the wires, we don’t know where they came from without holding the RECs. The RECs are our legally-recognized certificate of authenticity for renewable energy.

Those RECs sell for $30-40/MWh for wind and solar. Without those RECs, these systems do not pencil compared to natural gas generation. Do not come at me with levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) numbers; I have read the power purchase agreements (PPAs), and you have not.

Currently, decarbonization is lowest on the priority for all but the most activist electric utilities, primarily because everyone loves saving the environment, but no one actually wants to pay for it.1 However, renewable energy technologies (and associated decarbonization regulations) are the change agent for electric utilities and organizations like ISO-NE. The ship has sailed, and the old ways are not coming back.

We must change.

Demand Response and Time of Use: Limited Solutions

Trading marginally less reliability for marginally more decarbonization.

Demand response (DR) and time-of-use (TOU) rates are both attempts by electric utilities to enable marginal decarbonization without fundamentally changing the structure or costs of electric grids. These measures exist because a significant portion of total costs of electric utilities—think 20-30%—are incurred at grid-level demand peaks. Because the electric grid is sized for the maximum instantaneous demand possible for the service territory, we have to pay for the transmission, distribution, and the (dirty, expensive) backup generation necessary for that peak. If we can reduce that maximum demand by asking customers to consume less at that time, we get outsize cost and carbon savings per kW reduced. Unfortunately, the costs of implementing these peak reductions mean they typically only break even relative to the status quo.

Demand response is when you let your electric utility touch your thermostat or electric car charger. These programs reduce or curtail your electric use for 2–4-hour windows, around 5 times per month. Because demand peaks are driven by heating and cooling, those peak events are, as a rule, during late afternoons in heat waves and early mornings during cold snaps. If these systems work well, you don’t notice. If they don’t, you call your utility to complain.

Time-of-use rates, by contrast, don’t involve utilities touching your stuff—instead, your electric rate changes based on the season or time-of-day. The idea is that you shift your electricity use towards cheaper times of the day or (better yet) program your thermostats and electric car chargers to do that for you.

These measures are both taxes on reliability, because they make your electric bill more complex and violate the peace of mind with which you simply turn on the lights. With a demand response program, your thermostat is no longer fully under your control. And with a time-of-use rate, you now have to think about when you do your laundry and charge your electric car. Sure, you can charge your car overnight, but in most time-of-use rates, “overnight” now means starting charging at 10 PM. But what if you just came home at 10% charge? Your car won’t be fully charged when you wake up.2

Utilities can mitigate these reliability taxes by allowing “opt-outs” for demand response peak events, or by offering time-of-use rates that are all carrot and no stick. But these weaken the core impetus of these measures. Customers fundamentally understand that these measures impinge on their freedom to use electricity whenever they want. We tell customers that it won’t make a difference most of the time, but that’s a dishonest argument, because utilities never let “most of the time” slide for our own decisions.

If customers want the carbon savings of demand response or time-of-use rates with less of the reliability tax, they can purchase a V2G electric car charger or a home battery energy storage system. That’s expensive kit, though. You won’t make that money back through demand response credits.

Spot Price Anarchy: Diamond Hands 💎🙌 on the Wires

Letting the electricity spot market find the equilibrium.

A more “honest” approach to demand response and time-of-use rates is simply to wire customers up to the dynamic price of electricity on the spot market managed by organizations like ISO-NE. For electric utilities, the price of electricity is a mercurial figure that changes on a five-minute basis. And if you’re a regular customer, there could be an angle to wiring your meter to that market and playing the same game I play for my day job.

Twitter account @paulkingmorris recently posted this exact sentiment:

If 23 hours [of the day] are -$50/MWh, and 1 hour [of the day] is $1,000/MWh, is it still free energy?

And he followed up with:

Free energy if you take it on our terms! Prohibitively expensive energy if you take it on your terms!

This is possible in the ERCOT system. Texas electricity supplier Chariot Energy offers a “real-time rate” to this end. You still get a bill from your normal electric utility, but the “power supply” or “fuel” charge is instead replaced by an aggregated number from Chariot that tracks not only how much electricity you used but also when you used it and what price it was at the time you used it.

A smart buyer can exploit this structure: buy a backup generator or solar-storage system, and if spot prices rise above a certain threshold, discharge electricity into the grid and get paid at that spot price. Charge low (or with on-site solar), discharge high. At minimum, you can autonomously cut your grid connection if the spot price hits, say, $1,000/MWh.

The downside risks were made apparent by the infamous 2021 Winter Storm Uri. Because the storm knocked so much generation offline, spot prices in Texas reached a $9,000/MWh base price cap, with some subregions seeing even higher prices. This turned into five-figure monthly electric bills for some customers.

Unleashing “spot price anarchy” would motivate the proliferation of low-cost distributed generation and storage. This is how you let The Market drive decarbonization, and it would work (up to a point). But it pushes customers from an arrangement where electric utilities weather the price shocks of power supply to an arrangement where those customers are left to wander into the red themselves. If you believe in homo economicus, there’s an angle here. But the behavior of crypto traders and hodling apes suggests that things might go poorly. Consider that I make vintage-Campagnolo3 money to make these exact decisions for tens of thousands of customers. Would you truly prefer to do my job in your free time?

Renewables Overbuild: The Abundance Agenda

Balancing reliability and decarbonization, at whatever cost it takes.

A more mainstream approach to grid decarbonization is simply to build more: more solar, more storage, more transmission lines, and (depending on political persuasion) more wind, nuclear, biofuels, and hydrogen. The argument du jour for this approach is Abundance by Derek Thompson and Ezra Klein, but think tanks like the Foundation for American Innovation (FAI), the Institute for Progress (IFP), and the Niskanen Center have been on this beat for some time.

This is where ISO-NE thinks New England is going. They released a report about what they think decarbonizing the grid would take, and I wrote about it February 2025:

There are two core challenges with this vision. The first was recently articulated by broken-clock venture capitalist Balaji Srinivasan: “One man’s abundance is another man’s overcapacity.”

In New England’s case, decarbonizing the grid will require installing hundreds of MW of new generation and storage annually. That is fundamentally expensive, particularly because each new MW of intermittent generation and storage will generate fewer MWh per year than the last one. But if we utilities want to cover every hour of demand for the grid, we will need to keep building until we are done. The falling costs of solar and storage only go so far to mitigate this.

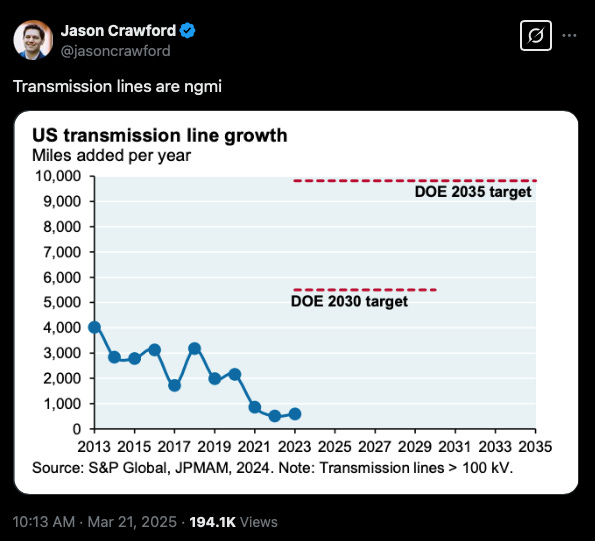

The second challenge is that energy abundance must be built. Think tank founder Jason Crawford recently tweeted a graph from a JP Morgan report that intimates how far behind the United States is on this front.

There’s a surge of think tank energy towards permitting reform, but that’s only the first step. What about materials processing, labor availability, financing, and shipping? Energy abundance—and abundance broadly—requires national reindustrialization in under a decade. I hate to spread FUD,4 but that’s a tall order.

As ISO-NE notes, this “renewables overbuild” would be eased by building nuclear reactors. I remain bearish on small modular reactors (SMRs) until I can actually buy one at my actual job as a utility resource planner, but a Westinghouse AP1000 AirDropped on the Merrimack Station’s transmission infrastructure would also work, provided one first sics Blackwater Contstellis goons on 350.org’s New Hampshire staff. I understand I have written against nuclear power, but it can have a place in a decarbonized grid, provided that one understands its tradeoffs:

However, lefty environmentalists aren’t the only energy extremists. I think wind generation is valuable to a decarbonized grid, but both American and European reactionaries have tagged it as “woke” energy. Notably, these reactionaries do not rail against solar with the same vitriol. Between the left-wing opposition to nuclear and the right-wing opposition to wind, solar and battery energy storage have become the easiest resources to permit, although New England would struggle to build enough solar generation to match our potential offshore wind capacity. One could see a future in which solar panels are connected to so many batteries that even winter nights are well-lit. But it will be more expensive and precarious than a system that included wind and nuclear.

Shale Supremacy: Zero Energy Poverty 2050

Maximum reliability at all costs.

At this point in the narrative, some commentators are inclined to respond, “And this is why green policies are doomed/delusional/a scam!” Robert Bryce and Doomberg voice this opinion on Substack, and Peter Zeihan (a self-described “Green who can do math”) offers a milder version of this view. In their estimation, nuclear and (more importantly) shale hydrocarbons can solve the United States’s short- and medium-term energy concerns, provided environmentalists get out of the way of industrial progress. Even if you’re a climate doomer, this angle is worth taking seriously.

Shale energy—both oil and natural gas—is the product of two interlocking technologies: hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling. These technologies were new and controversial in the Obama days, but they have improved dramatically in cost and output in the intervening fifteen years. Today, they are directly responsible for low energy costs in the United States. I know your energy bills feel oppressive, but they’re two to five times worse in Europe.

New England now depends on shale natural gas. We have three links to the shale boom: two pull from the Marcellus shale fields in western Pennsylvania, one pulls from the Texas hub of shale production. These pipelines have superseded oil and coal use for both heating and electricity, because shale gas has proved to be cheaper and lower in emissions, including CO2, SOx, and NOx. If you’re a moderate Green, shale is an unmitigated victory for decarbonization. It’s not zero emissions, but it is the single greatest driver of reduced emissions, reduced pollution, and reduced energy burden for regular people. And we’re not running out soon. Shale exploration and production (E&P) companies frequently say they have three decades of reserve on tap, but from what I’ve heard from the Twitter gas traders, that’s a polite fiction to ward off acquisition. There’s almost certainly more.

Applying a “shale supremacist” policy to New England would require one of two approaches:

Increase pipeline capacity to New England by another 1 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d). This is straightforward, expensive, challenging to permit, and potentially overkill outside of winter cold snaps.

Revise the Jones Act to allow liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the Gulf of

AmericaMexico to reach Boston. Currently, the Jones act requires all ships traveling between American ports to be built, crewed, and owned by Americans. However, the United States doesn’t build merchant marine ships at scale, meaning Boston must compete with the Germans and Koreans for marine LNG from Qatar, Russia, or Trinidad & Tobago.

Interestingly, ISO-NE CEO Gordon van Welie suggested a similar set of ideas in some 25 March 2025 remarks to the US Congress Energy Subcommittee:

To the extent offshore wind is delayed, I think the conversation will turn to, “What are the other possibilities [for energy supply]?” The options on the table would be additional pipeline infrastructure, [allowing] dual-fueling [for natural gas plants to run on fuel oil]…One thing Congress could help us with here is the Jones Act…It would be helpful if New England could access domestic LNG; we export it at $6/MMBTU but we’re having to import it at $35-40/MMBTU [from international markets].

Extreme, Haterade-chugging anti-Greens like the aforementioned Bryce and Doomberg would have us unleash Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II “Warthog” attack aircraft on Vineyard Wind out of pique, but quick-response gas peaker plants would prove a valuable backstop to an electric grid otherwise built of intermittent renewables. When the sun goes down and the wind speed falls, these (relatively) clean-burning fossil fuel backups can fill a role otherwise filled by an overbuild of marginal-production renewables and battery storage.

If you simply want more electricity to meet increasing demand, shale gas is a powerful option: low-cost, low-carbon, flexible, plentiful. The current Secretary of Energy Chris Wright holds this opinion—his goal is not Net Zero by 2050 but Zero Energy Poverty by that same timeline. And he thinks that requires fossil fuels:

But I’d argue that the solution cannot only be fossil fuel generation, because the turbines that actually convert combustion into electricity are on back-order through at least 2030. For the next ten years minimum, we must be very careful about how we dispatch fossil generation, simply because it cannot cover all the incoming electric load growth from the new factories, data centers, and electric vehicles we say we want:

Additionally, adopting this approach would require New England to abandon total decarbonization as a political project. We need not accept runaway climate change, but we may decide that our money is better spent on seawalls and stormproofing than on total decarbonization. Ignore what Big Oil says. Remember that humans settled Siberia and Dubai. Look at your electric bill instead. Would you quintuple that number in the name of 1.5°C? And on the flipside: are you willing to give up on a political project simply because it’s expensive?

Microgrid Degrowth: Light of the World, City on a Hill

Total decarbonization at all costs.

Some readers will look me in the proverbial eye and reject that tradeoff. Instead, they will espouse a series of talking points like:

Capitalism, market dynamics, and financial thinking broadly are incompatible with decarbonization.

The issue is that advanced economies use too many resources, full stop.

The solution is a circular economy that priorities repairable goods, ecological restoration, local community, and a coexistence with the landscape informed by indigenous practices.

The energy requirements of this world can be met by decentralized and modular microgrids built primarily from village-scale solar-storage networks.

Taken as a whole, this is the post-industrial ideology known as degrowth. It’s a Malthusian, post-Marxist approach to political economy that—although no one frames it this way—argues for a dignified poverty in reaction to the present decadence of factory farms and microplastics. Degrowth advocates a return to cotton-sack dresses5 and venerable Dutch bicycles through agrarian villages, transformed by a limited application of modern technologies. If there’s not enough energy, the degrowthers may say, then do without for a few hours.

In practice, degrowth advocates do not make these arguments—instead, their advocacy is more spiritual and aesthetic: cottagecore, solarpunk, a cozy post-apocalypse on a farm with your loved ones. To be a degrowther is less to make an argument of political economy and more to exclaim that you might throw your phone into a lake. But to be clear, degrowth asks one to turn away from modern industrialized wealth. The alternative to disposable plastic unrepairable everything is to have items too expensive to throw away. Glass milk bottles, the death of takeout food, and far fewer electronics.

In this scenario, the role of an electric utility would dissolve. You would have your own microgrid instead, a network of solar panels, water wheels, and battery energy storage systems, all strategically linked (or unlinked) to a collapsing grid outside your community. And in 2025, you can build one at great expense, as I described in February 2025:

Such a project would become a city on a hill in the John Winthrop, salt-and-light, Matthew 5:13-166 sense: a quiet village connected by locally-farmed crops, a near-circular economy of repairable homegoods, a renewable and distributed energy system, and an insular “ordered liberty” befitting New England’s Congregationalist cultural heritage. But at current prices, it is only feasible as an enclave for the hyper-rich. Right now, these people see fit to keep their black Audis, but should the lights truly start to flicker, the hyper-elite of Beacon Hill may yet flee to Stowe to wait out the end of the world.

Wood Stove Degrowth: The Great American Gumption Shortage

Balancing low cost and decarbonization, at the cost of reliability.

Energy technology is the hardest part of the degrowth pitch because of the ugly reality of industrial production. The steel, copper, adhesives, and polysilicon of solar panels require a fully industrialized, energy-intensive supply chain. Virgin steel particularly must be produced with fossil fuels (primarily coal coke) because the carbon is necessary to turn iron into steel. The alternatives are not only expensive but also scarce, and many degrowthers seem too reflexively disgusted by heavy industry to seriously consider addressing this.7

But a more down-to-earth option already exists. Substack writer A.M. Hickman is living it:

Our 1,100 square-foot, two-story, three-bedroom home in the Adirondack Mountains cost us $33,000 cash. It’s got a 1,000 square-foot barn, a brand-new propane furnace, a wood-stove, and two giant porches, all nestled in on a tenth-of-an-acre village lot in a 250-person village in the wilderness. Our town has a daily bus line to the County Seat for groceries, and it’s got a gas station, liquor store, bar, library, Catholic Church, school, and 76,000 acres of forever-wild wilderness preserve within walking distance, including several islands and waterfalls. Our monthly taxes, sewer, and water bills altogether total $115 per month. We own it outright, with no bank, no interest, no nothing — it’s ours, for a monthly price that’s about on par with a single night in a Motel Six. And beyond any reasonable doubt — we could not have built this place for $33,000. [Source]

Hickman doesn’t own a car. By his account, he can ride his bike to the center of his village and a bus everywhere else. He’s as anti-car as many left-wing degrowthers. As it stands, Hickman’s Scope 1 carbon emissions are well below an equivalent suburban American. If he were to remove the propane furnace and commit to a wood stove, he would achieve near-total decarbonization. Alternately, if he installed a limited-use propane genset (or a very small solar-storage unit), he could completely reject the electric grid. If you were to expand to Scope 3 emissions, there’s a decent chance that fixing up his house in the Adirondacks emits less CO2e over a decade than tearing it down and building a passive house on the lot.

You, right now, can follow Hickman’s example—in fact, he wants you to. If you’re a degrowth hardliner, I recommend you read Hickman’s work much more closely and ask yourself, seriously, what you would lose by following his advice, pooling funds with your loved ones, and “[buying] an old hardware store in small-town Nevada.” The queer commune many poasters say they want is eminently reachable.8 And if you—like me—still want road bikes and boutique espresso, there is a panoply of gorgeous New England villages to consider. If you, the reader, want the “microgrid degrowth” described above, this is the interim option for building utopia today. Start by building “wood stove degrowth,” and wait for the energy technology to fall in price.9 But this a lifestyle that requires trading comfort, clout, and apathy for a miniature Kingdom of God, and I agree with Hickman that it requires a hardscrabble moralism that was a part of the American character but is uncommon today:

Flickering Lights: The Fantasy of Keeping Rates Low

Inaction is cheap, in a sense.

Despite my attempts toward neutrality, I clearly have my opinions about all these proposed strategic goals for electricity in New England. I am in political coalition with the proponents for abundance, even as I doubt the feasibility of their goals. I am sympathetic to the shale supremacists’ arguments but question why they’re all massive haters. I advocated a spot-price electric rate at my previous job, figuring that a few customers would like it. And I am waiting for someone to lead by example on degrowth, to let their light so shine before us, so that we may see their good works and glorify their ideals which are in heaven.10

But inaction is not a viable option.

There are a few municipal utilities in New England that pride themselves on low rates. They still like reliability, but they brag about how low their rates are and how infrequently they raise those rates. But between behind-the-meter solar generation, the proliferation of electric vehicles, the increasing volatility in oil and gas prices, the slow-dawning knowledge that grid infrastructure absolutely will be targeted in a great-power conflict, and the shifting challenges of storms escalated by climate change, merely keeping up reliability will require raising rates.

We’re in the jungle now. The halcyon stability (so I’m told) of the ‘90s and ‘00s is long gone. And frankly I question how much of the past era’s “low rates” was downstream of deferred maintenance. Notionally, utilities need not rise proactively to the current challenge. We can slow-walk decarbonization, suppress distributed generation, double-down on gas futures, and insist that Beacon Hill or Hartford or God forbid Montpelier will “see reason” and roll back climate regs. But that vision of the future of the grid is most delusional of all.

But we don’t…need to keep the lights on, right?

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of their current or previous employers or any elected officials. The author makes no recommendations toward any electric utility, regulatory body, or other organization. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, the author has not independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author assumes no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

At a prior position, we offered a “renewable choice” option that allowed people to willingly add a surcharge to their bill—think $10-20/month—to make their electricity renewable. Out of tens of thousands of customers, at most a few hundred signed up.

Worse, these time-of-use rates can get very complex—in California, you’ll see three-tier rates with seasonal and electric vehicle modifiers, which makes the question “what is my electric rate” fundamentally unknowable.

For non-cyclists, Campagnolo makes Italian bicycle components. Every stereotype about Italian engineering applies. I’m obsessed with it.

Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt

During the Great Depression, many families repurposed empty sacks of flour as fabric for homemade clothes. Flour distributors caught on to the practice and manufactured those sacks out of colorful fabrics to facilitate this reuse.

From the Geneva Bible:

Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savor, wherewith shall it be salted? It is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men

Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on an hill, cannot be hid.

Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick, and it giveth light unto all that are in the house.

Let your light so shine before men, and they may see your good works, and glorify your father which is in heaven

If you’re not so squeamish, train up as a chemist, materials scientist, or industrial engineer and seek out ways to decarbonize cement, steel, fertilizer, and industrial inputs. That’s the highest-leverage vector for a single person to fight climate change. Remember, even Lenin and Mao valorized steel production.

I understand that many of these middle-of-nowhere locations do not necessarily have LGBT-friendly legislatures. But the flipside of these locations is that the legislatures are very far away. In isolated American mountain hamlets, there are probably more shotguns than cops per capita. For millennia, people have migrated to the hills because governments can’t reach them there.

I admit I haven’t done this myself, primarily because I’m not an explicit advocate for degrowth. My goal with this article is to name the proposed futures of the electric grid and briefly describe the effort and tradeoffs necessary to make them happen. If you espouse one of these grid futures but refuse to pay their associated costs, then you’re a liar.

I truly am sympathetic to the cultural diagnoses of degrowth advocates. Even Millennials and Zoomers who aren’t fully degrowthers should make peace with the reality that we are poorer than our parents, and instead we should valorize frugality, community, and service to others. I, certainly, am making peace with the cards I have been dealt. I fear, however, that we are all hypocrites, railing against the purported selfishness of our Boomer and Gen X parents, dreaming of a sustainable future, but fundamentally still addicted to the accumulation of kitsch, flash, and largesse to flex on our mutuals.

I found this to be very entertaining and refreshing difference in perspective, coming from a Florida Utility we have the same similar gas constrained grid.

I will say I think peter zeihan oversells the impact of the jones act, even if New England or Florida could import lng to get around pipeline constraints you would first need to contract at the Internataional lng price just to get the ship to come to you.

And in the event of a serious price run up in Europe the tanker might even break its contract with you and divert the ship to Europe - the penalty they pay to you may be less than what they stand to gain diverting.