Taking Spot Price Anarchy Seriously

Contra a specific booster of microgrids

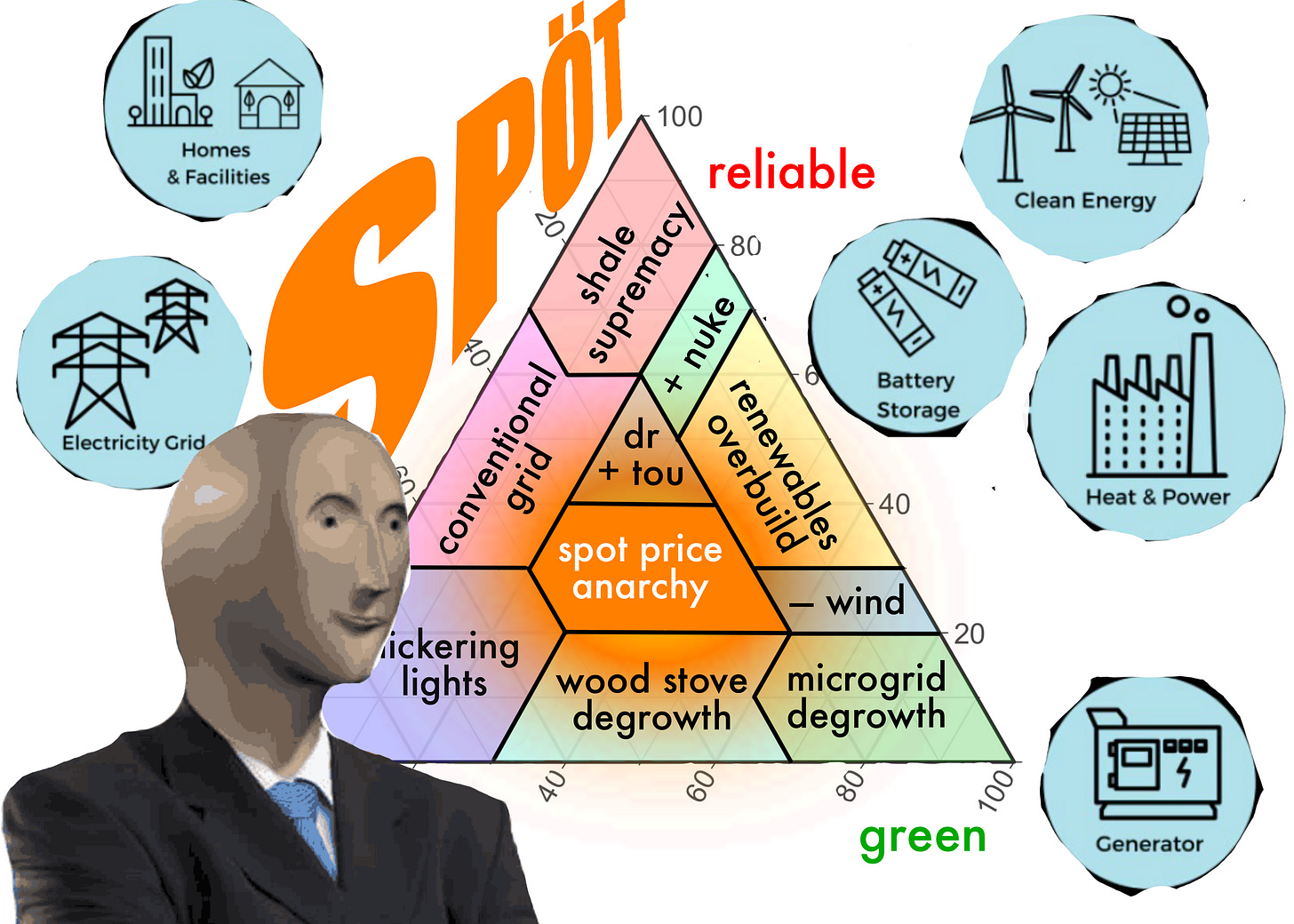

My most comprehensive piece for Energy Crystals is a “soil-chart” rundown of the different futures of the electric grid, balancing the tripartite priorities of maintaining reliability, mitigating costs, and enabling decarbonization. It’s pretty good!

In the middle of that chart, I named an ideology I glibly called spot price anarchy:1

For electric utilities, the price of electricity is a mercurial figure that changes on a five-minute basis. And if you’re a regular customer, there could be an angle to simply wiring your meter to that same market and playing same game I play for my day job…A smart buyer can exploit this structure: buy a backup generator or solar-storage system, and if spot prices rise above a certain threshold, discharge electricity into the grid and get paid at that spot price. Charge low (or with on-site solar), discharge high. At minimum, you can autonomously cut your grid connection if the spot price hits, say, $9,000/MWh.

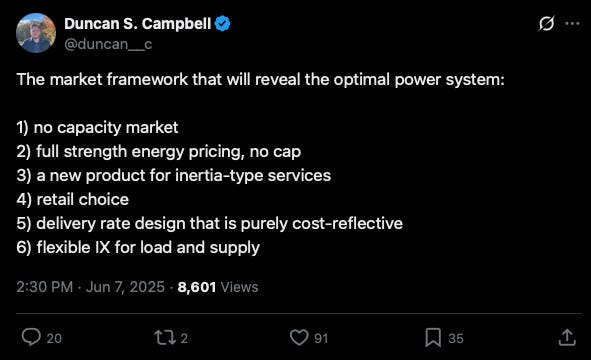

I gave the ideology under 500 words of thought, but a recent2 tweet by Duncan Campbell gave a sharper, bolder account that warrants a more serious post:

Duncan Campbell

7 June 2025, 2:30 PM

The market framework that will reveal the optimal power system:

1) no capacity market

2) full strength energy pricing, no [price] cap

3) a new product for inertia-type services

4) retail choice

5) delivery rate design that is purely cost-reflective

6) flexible [interconnection] for load and supply

This is a clear-eyed account of spot price anarchy, from someone who 1) believes in it and 2) knows what a wholesale electricity market is. Campbell is—unlike a lot of people poasting about energy—a professional. We even have LinkedIn mutuals! He deserves a professional rebuttal.

But First, Some Ad-Hominem Comments

Duncan Campbell is the VP of Project Analysis and interim VP of Project Development at Scale Microgrids. This company will sell you, well, a microgrid: a full-stack energy network that includes some combination of solar panels, battery energy storage, electric vehicle charge management, and fossil backup generation. The secret sauce to a microgrid is the controls software, which would integrate grid reliability and market data, local solar production and energy storage, and on-premises energy needs into a single dashboard that your Director of Facilities can harrumph at. These microgrids are great for campus complexes—colleges, yes, but also research parks, industrial facilities, and municipal EMS building networks. These things are probably single-digit millions of dollars in capital expenditure for a decent-size install, because they’re fundamentally Cadillac energy systems—solar and batteries and gensets and building management systems (BMS) and that all-important unification software. If you were happy with your electric service, you wouldn’t bother with any of this business. If you just wanted to save money, you’d get a solar system subsidized by a grant and/or a tax credit. If you were paranoid, you’d keep a diesel genset or two on retainer. But installing everything is a stiff expense unless 1) you need to keep online until FEMA shows up or 2) you want to tell your electric utility to kick rocks.

Campbell also co-founded a DER Task Force that’s poasting about the glory of distributed energy resources (DERs)3 in service of an energy future with more market-pilling and decentralization. The DERTF seems like a cool crew. I might even attend a meetup someday!

All this is to say that Campbell has a financial interest in his ideology. I think the ideology came first—and if so, there’s honor in staking your career on your beliefs. But the business viability of Scale Microgrids—and the health of Duncan Campbell’s BD pipeline—is linearly proportional to the degree that the general public endorses spot price anarchy, or “Retail Choice 2.0,” or an electric utility death spiral.

Okay. Let’s talk substance.

Energy Markets Without Guardrails

Campbell’s proposals to 1) remove capacity markets and 2) remove price caps on wholesale electric costs seek to push electricity companies away from their habit of hedging on everything. Capacity markets hedge against the risk of insufficient supply by paying for generators to sit idle for 99% of the year. That way, those generators can be ready for the 20-90 hours of the year that the grid really needs them. The benefit is that the grid doesn’t see brownouts that force grid operators to decide who doesn’t get electricity for a few hours at a time. The cost is paid up-front, typically to fossil-fuel generators, frequently to the oldest and most polluting derelicts in the generation fleet.

Similarly, price caps on wholesale energy limit the upside potential for electricity generators who do run during nightmare supply shortages. Right now, those price caps are still pretty high: $5,000/MWh in ERCOT, $2,000/MWh (for day-ahead bids) in ISO-NE, compared to normal wholesale prices between $20-50/MWh. But if a 5MW/20MWh battery could discharge 15 MWh of electricity in an environment when electricity prices reach, say, $13,000/MWh, that resulting $200k payout would be enough to cover annual O&M costs for the battery. Alternately, if you have a Scale Microgrids™️ full-stack energy solution on your commercial campus (purchased at $0 down), the savings you get from relying on that microgrid during the above nightmare supply shortage might singlehandedly flip the economics of that project from red to black. Heck, you don’t even need the lifeline! Just get whacked by that shortage so hard that you sign on the dotted line out of fear that it happens again.

Of course, even if you didn’t purchase a microgrid for your home or business, you can always cut your electric meter during such price spikes.

This position isn’t entirely sinister.4 If you truly, unequivocally, believe in the power of a market to adequately price risk, then letting the Magic Line go crazy is ideologically consistent. If the price of electricity is too high, then disconnect your meter above a certain price threshold. If the value of 99.9% or 99.99% uptime is really that high for you (whether you’re a data center or a grandma with an oxygen tank), then you can buy a battery and hedge your risk for yourself, at the risk profile you like, instead of letting the House (utility resource planners like me) decide how much risk you can handle.

My glib issue with this approach is that I’m a bear. I’m short AI, I’m short solar-storage, I’m short Trump 2.0, I’m short my risk of personal injury, I’m short America.5 I like capacity markets, and price caps, and putting bears like me in charge of power supply purchases for normie electricity consumers.

My real issue…I’ll get to at the end.

Ancillary Services & Flexible Interconnection

Back in May, I talked about FERC Order 904, which banned grid operators like ISO-NE from paying for reactive power balancing:

Campbell would recommend bringing that back, and in fact putting more money into reactive power (voltage) and frequency regulation. He brings up inertia in specific, but I’d argue that large-scale batteries are also a great option for maintaining power quality. There are some nuances about voltage regulation versus frequency regulation, but broadly I’m in agreement with Campbell here.

That said, he didn’t use the term of art “ancillary services.” I worry that he, like the grid-future researchers a nearby university, has never spoken to or read documentation from an ISO or RTO.

As for flexible interconnection, there are a few different things Campbell could mean by this: anything from cluster-study interconnection (which is already FERC doctrine) to asking grid operators to accept rowdier risk profiles, to setting interconnection agreements that assume a load might be shut off during some extent of peak time. Please correct me here.

Retail Choice 2.0

When I hear retail choice, I think about the junk mail I get about “buying renewable energy” through my electric bill. Retail choice enables the power supply equivalent of investment funds, which often contract with Massachusetts municipalities instead of individual customers. I’ve heard mixed-to-negative-to-astroturfed reviews about the policy.

When Campbell says retail choice, he likely refers to Allison Bates Wannop’s “Retail Choice 2.0,” which pitches a suite of business models allowing for customers to pay for more complex rate models, from British Octopus Energy’s “Smart Tariffs” and wind farm “fan clubs” to gimmicky sales tactics like comping beers for customers who do demand response. Frankly, I think the gimmicks are nice—a free beer would honestly be a better incentive for demand response than a five-dollar bill credit. But I don’t trust the companies that would play in this space. Specifically, Wannop’s examples disproportionately come from British power suppliers, and I do not see the United Kingdom as a functional model for energy policy. If Whitehall likes it, it’s an automatic red flag in my book.

Cost-Reflective Electric Rates

Campbell’s recommendation of a “delivery rate design that is purely cost-reflective” harbors an accusation: that electric utilities lie to customers about how much electricity costs.

Guilty as charged. We do lie.

A normal (New England) residential electric bill has two components:

A monthly “flat” charge of $5-12

A volumetric charge of $0.15-0.30/kWh, split out into a bunch of line items that confuse customers

This does not reflect our cost model. The idea of a “retail cost per kilowatt-hour” is a Dr. Seuss fairytale held in place by papercraft assumptions about whom our residential customers are. If I wanted to design a truly cost-reflective residential electric rate, it might look like:

A monthly “flat” charge of $40

A non-coincident demand peak of $3/kW-month, measured at monthly customer meter peaks

A coincident demand peak of $13/kW-month, measured at monthly ISO-NE system peaks

An annual demand peak of $4/kW-month, measured at the annual ISO-NE system peak and amortized over the next 12 months

A fuel charge that dot-product vector-multiples hourly customer use with hourly wholesale spot prices, into a net charge of $0.03-0.05/kWh

I used to work utility customer service. I often took calls like “I just got an electric vehicle. How much will it increase my electric bill?”

The customer is asking for a number. In US Dollars per month. From a human being. Now. Any deviation from a friendly voice on the phone saying “about fifty bucks a month” will be interpreted as:

Hi. I’m your electric utility. I think you’re dumb. In fact, I hate you, personally. I’m going to take your money, burn it in Vegas, laugh at you by name, and raise your rates again.

Alternately, read Max Read’s piece on “Pricing the Future” and tell me he wouldn’t see spot price anarchy as another brick in the wall:

But in practice, modern dynamic pricing—especially when deployed in concert with search and surveillance—is often explicitly hostile to consumers, steering them toward more expensive options and throwing out highball quotes.

It’s also, in all cases, implicitly hostile to consumers, obligating a much higher level of attention and involvement to the simple act of buying something--or, as with airline tickets, extracting a “tax” on anyone without the time and inclination to do so.

…

The transformation of relatively stable prices into individualized, tech-driven moving targets pushes us even further into the realm of speculation and wagers. Attaching volatile, up-to-the-minute surveillance-driven prices to any good or service is a good way to put it in the same basket as securities, crypto tokens, wagers, and online reputations. What happens when buying anything at all requires the same level of attentiveness, care, and planning with regard to prices that most of us bring to flying commercial, buying concert tickets, or speculating on securities? A life spent trying to predict when bread and eggs are going to be the cheapest, and which family member’s credit score will earn them the best deal. [Emphasis mine.]

Of course, I’m being glib again. Every utility rate consultant I have spoken to has advocated increasing monthly “flat” charges to reflect real “first kWh” plant costs—about $40 per residential customer per month. Those non-coincident demand peaks are standard billing practice for commercial customers (although many small business owners get bamboozled by them anyway). And that vector-multiplied “real time rate” has been tried in New England. The New Hampshire Electric Cooperative (NHEC) called it a Transactive Energy Rate.

It deserves a piece of its own.

Stupid People are Electric Customers Too

The reëmergence of Donald Trump unlocked a flurry of IQ-posting, including the meme I stole above from someone who probably would have found GamerGate memes repulsive. I think much of the appeal is in the glee of calling someone biologically, intractably stupid, but let’s take that frame seriously: stupid people are electric customers too.

Every January and July, utility customer service desks get inundated by high bill complaints that follow the cadence of:

CUSTOMER: “Did you raise my rates?”

HELP DESK: “Sir/Ma’am, do you see the number on your bill that says ‘kWh?’”

CUSTOMER: “Yeah, it says 1,200 kWh.”

HELP DESK: “That is your electric usage. Last month, that number was 800. Our electric rate did not change, but that number did. That’s why your electric bill went up.”

CUSTOMER: “Oh.”

Stupid people are electric customers too.

Many electric utility customers lack the intellectual horsepower to grok what a kilowatt-hour is. Many more lack the time and breathing room to figure out what a kilowatt-hour is. I literally work for an electric utility, in the part of the office that sets electric rates, and it’s an active hassle to figure out a utility’s cost-per-800-kWh without a sample bill in front of me. If I can’t figure out an electric rate without a half-hour of billable focus, who can do so at all? Do we want to throw demand charges and real-time rates on top of that?

Electric utilities must serve Nissan Altima drivers. We must serve the functionally illiterate. We must serve people who spend five seconds looking at their electric bills and resent the expectation that these bills need more thought. One of the responsibilities of being a regulated natural monopoly is that we are not allowed to turn away a customer because they’re too dim to read three pages. And although regulators may not ask, we have an obligation to treat these customers with respect. Campbell may cheer on an electric utility death spiral in which customers who can get a microgrid do, but I know the likely profile of the last people trapped in that death spiral.

Stupid people are electric customers too.

The Librarian of Celaeno says it well:

The thing about us people on the port side of the bell curve is that, the dumber you are, the scarier life is. You know there are people much smarter than you, but you lack the imaginative faculties to really comprehend what that means. If your IQ is 85, someone who’s a 100 sounds pretty much like someone who’s 120, and so on. You don’t think about the details. You just know that there are a bunch of people who wear ties and work jobs where people care what they think, and they have an outsize influence on your life, one you can’t really fully grasp…People on that level—my people—live in a world where everyone is trying to get over on them. The dumb are on the receiving end of every scam possible: payday loans, rent-to-own furniture, OnlyFans, seed oils, etc. They know their fellow idiots are out to get them, and that’s bad enough. But they also know that the smart folks want their money and energy, and unlike with their peers, clever schemers are both unpredictable and unfathomable.

The Librarian is talking about me. And he’s talking about Duncan Campbell.

My job as a utility energy analyst is to serve everyone. Even the stupid people, because—say it with me—stupid people are electric customers too.

And stupid people deserve electric rates that make it damn clear that I’m not out to get them. Itemized line items are counterproductive. Beautiful quantitative models read like threats. But having spoken to these customers, they do respond well to:

I’m listening to you. I know what these numbers mean. You don’t have to. I know it’s a lot of money. I’m working on it. I’m on your side.

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only.The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of their current or previous employers or any elected officials. The author makes no recommendations toward any electric utility, regulatory body, or other organization. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, the author has not independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author assumes no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

I’ve read enough Existential Comics to know anarchy is supposed to mean something else, but shut up

Recent by professional standards, not by Twitter standards.

The short definition of DERs is “what if all the solar panels and batteries talked to each other on the cloud.” The short rebuttal is, “on whose API standards?”

It’s only pretty sinister.

I see your “Nothing ever happens” and raise you a “Nothing ever works”

Some excellent insight here! I can see price signal and efficient markets as effective tools as many economists would tell you. But real world results show how hard it is to implement becuase humans are so... human. It made me think of homer simpson https://youtu.be/lgi1LFVWurg?si=BZeBEZhoL9rq4n8V People don't want to become day-traders just to keep their lights on.

For perspective though, look at riparian water rights in California. we're locked into a riparian water rights system that, on its face, seems to incentivize wasting water during a drought. It's logically baffling, but it persists because of the immense human and political history behind it. Your article is a great read as I research water markets, which seem like a potential solution but, as you've shown, are fraught with these same human-centric challenges.

great piece definitely related to that explaining rates to the average user, coworker would always get the calls from landowners doing solar projects. I loved listening in it was always funny to me how people contemplating investing lots of money into projects were always put upon by some pretty simple questions.