ISO-NE Can't Say No to Their Stakeholders

The Planned Economy, Part 3: The Deactivation Reforms

This is Part Three of a three-part series. The previous two parts are here:

If I had to pick a timeframe for when the Old Grid of the ‘00s and ‘10s died, I would pick the back half of 2017. During that time period, the Tesla Model 3 started deliveries, soon becoming one of the best-selling vehicles on the planet, while Hurrican Maria flattened Puerto Rico’s electric grid. Maria was the first natural disaster I remember being defined by a climate narrative, particularly because it immediately followed the most ominous satellite photo I’ve seen in my life:

In that six-month timeline, the most compelling case for electrification and the most compelling case for climate action rocked the utility world. It motivated me to pick this line of work.1

I think ISO-NE would pick a more specific date: the March 2018 withdrawal of the behemoth Mystic Generation Station from the 13th Forward Capacity Auction. I talked about the Mystic Generation Station on Part 1 of this mini-series, because I find it important for explaining ISO-NE’s thinking for the next ten years. Not only did its fall poke at ISO-NE’s deepest fear—running out of electricity—but it also tore through all of ISO-NE’s existing measures to prevent it. This failure snuck past ISO-NE’s repository of crystal-ball operators, could not be patched over with rebalanced transmission operation, and most pressingly was a market failure. The core ideology of ISO-NE is that a sufficiently regulated market can drive down electricity costs without sacrificing reliability. The Forward Capacity Market exists because of that ideology, under the claim that selling auction-priced, forward-guaranteed cash flow to giant power plants would ensure that the power plants would be there.

And instead, ISO-NE started 2018 fearing that come 1 June 2022, New England was one heat wave or cold snap away from a brownout. So it acted, inking a deal with Exelon, the then-owners of Mystic Generation Station, to pay whatever it takes to keep that 2 GW power plant online until ISO-NE could muster an alternative. Unfortunately, “whatever it takes” was, in fact, a lot of money. I managed to find the final payout figures for Mystic, as well as a mostly-complete rundown of Mystic’s operational status during this period.2

June 2022: Load obligation: 9.8 million MWH. Paid $12.7M. Status: Predominantly offline

July 2022: Load obligation: 12.4 million MWH. Paid $47.5M. Status: Tank congestion management

August 2022: Load obligation: 12.4 million MWH. Paid $3.5M. Status: In-merit operation

September 2022: Load obligation: 9.3 million MWH. Paid $11.6M. Status: Predominantly offline

October 2022: Load obligation: 8.8 million MWH. Paid $11.9M. Status: Predominantly offline

November 2022: Load obligation: 9.2 million MWH. Paid $53.6M. Status: Tank congestion management

December 2022: Load obligation: 10.5 million MWH. Paid $33.5M. Status: Tank congestion management

January 2023: Load obligation: 10.4 million MWH. Paid $150.2M. Status: Tank congestion management

February 2023: Load obligation: 9.4 million MWH. Paid $104.9M. Status: Tank congestion management

March 2023: Load obligation: 9.6 million MWH. Paid $45.9M. Status: Tank congestion management

April 2023: Load obligation: 8.3 million MWH. Paid $13.7M. Status: Predominantly offline

May 2023: Load obligation: 8.3 million MWH. Paid $35.6M. Status: Tank congestion management

June 2023: Load obligation: 9.2 million MWH. Paid $11.7M. Status: Predominantly offline

July 2023: Load obligation: 12.1 million MWH. Paid $21.8M. Status: Tank congestion management

August 2023: Load obligation: 10.5 million MWH. Paid $15.1M. Status: Tank congestion management

September 2023: Load obligation: 9.6 million MWH. Paid $10.9M. Status: Predominantly offline

October 2023: Load obligation: 8.7 million MWH. Paid $11.1M. Status: Predominantly offline

November 2023: Load obligation: 9.2 million MWH. Paid $17.9M. Status: Tank congestion management

December 2023: Load obligation: 10.0 million MWH. Paid $25.8M. Status: Tank congestion management

January 2024: Load obligation: 10.9 million MWH. Paid $26.5M. Status: Tank congestion management

February 2024: Load obligation: 9.5 million MWH. Paid $36.7M. Status: Tank congestion management

March 2024: Load obligation: 9.3 million MWH. Paid $54.2M. Status: Tank congestion management

April 2024: Load obligation: 8.3 million MWH. Paid $10.7M. Status: UNKNOWN

May 2024: Load obligation: 8.7 million MWH. Paid $10.7M. Status: UNKNOWN

Between 1 June 2022, when Mystic’s original capacity obligations lapsed, and 31 May 2024, when it finally shut down, load-takers paid $778 million to keep this plant nominally online. And during that two-year period, it almost never functioned normally. For “large” municipal utilities covering tens of thousands of meters, this looked like $2-4M over two years against annual revenues of $60-120M. I’d wager that this rough percent-spend scales to all utilities, suggesting that the Cost-of-Service (COS) payments towards this sickly dog of a power plant singlehandedly increased New Englanders’ electric bills by 1% for 24 months.

…By the way, the owner of the Mystic Generating Station changed between inking this deal and sending the funds. So, Constellation Energy got this sweet deal without even doing the negotiations beforehand!

Words can describe the weight of these payments—but none that I will print on this blog. ISO-NE knew their Capacity Auction Reforms had to address it…even if they can’t stop power plants from being money pits.3

The Reliability Review

Even with the outgoing Forward Capacity Market, power plants are not allowed simply to fall off the map—a generator must run through a system reliability analysis before it is allowed to die. In particular, the system owner must consult with ISO-NE’s Internal Market Monitor (IMM) to map out the consequences of shutting down this power plant, with respect both to stability of transmission lines and to whether the grid will run out of electrons during peak times. The IMM also reviews the financials of the power plant to confirm that they really are as bad as the owner claims.

The IMM will send suits to your address for a de-listing as low as 20 MW. As a generator, that’s smaller than a single jumbo-jet engine nailed to the ground. As load, that’s something like the peak demand of Great Barrington, MA.4 But ISO reckons that out of 1300 generators on their radar, under 200 break that threshold.

ISO-NE’s reforms will maintain this core structure,5 but the context will shift slightly: A faster input, and a planned punishment for exploiting what ISO-NE calls market power.

(New) Highways to Hell

The prior version of this deactivation process required a four-year lead time and a de-list bid. The Mystic Station was no exception: it announced closure in 2018, crashed out of the Forward Capacity Market in 2019, and was supposed to shut down in 2022. That de-list bid was important, because it offered a threshold price for the power plant—if the final capacity price fell below a listed “break-even” price for your plant (and if the IMM approved that price after rifling through your finances), then you were allowed to exit from the market. But if your power plant could clear the market, then ISO-NE would deem your plant’s finances not to be bad enough to justify deactivation.

In the new structure, ISO-NE will shrink that lead time to two years and eliminate the de-list bids. Instead, if the IMM suspects foul play, they’ll sneak a “proxy bid” price for your power plant into the capacity market and see what it does. Put another way, if the ISO-NE Internal Market Monitor does not like your bid, they’ll write one for you and submit it anyway. The “In Soviet Russia…” jokes write themselves.

The (Failed) Market Power Charge

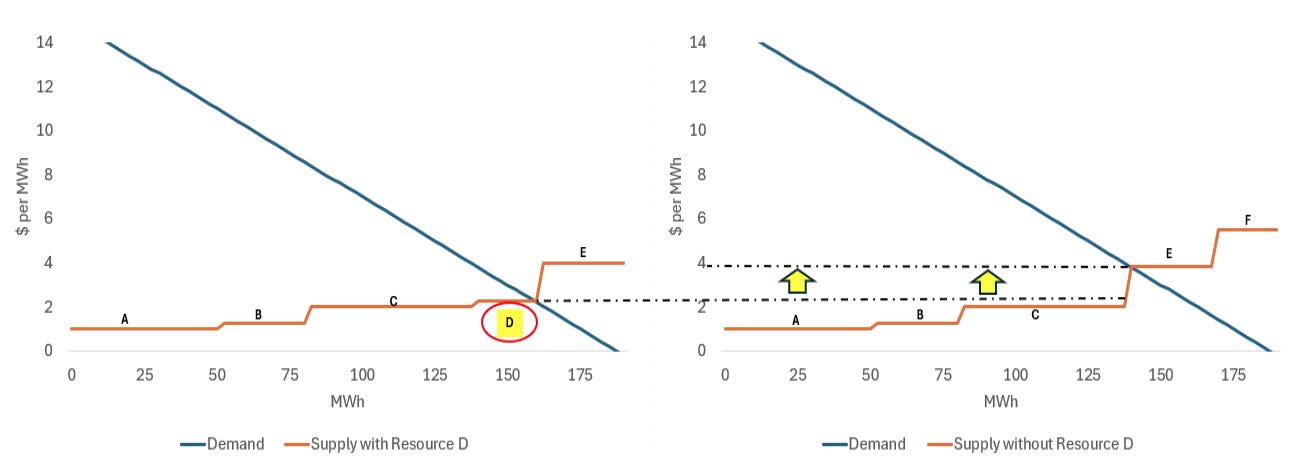

Imagine you don’t own one power plant—imagine you own three instead, labeled A, C, and D. You move to shut down Plant D, and the rubes at ISO-NE let it happen. But now there’s less supply for the capacity market! Economics happen, and the price of capacity shoots up. You no longer get capacity revenue from Plant D, but Plants A and C are still in the market and benefit from the increased price of capacity. As a result, you end up with more revenue from your two remaining power plants than you did when you kept Plant D on your portfolio.

ISO-NE calls this market power. They worry that a sufficiently large market player would see this math in advance, shutter a perfectly good power plant, send capacity prices to the moon, and pocket the payout from the rest of their portfolio. Even in the current capacity market structure, the IMM was checking for this effect with a net portfolio benefits test. But now, ISO-NE wants to add a potential fine on the back end. If your net portfolio benefits test comes out with a positive projected payout, ISO-NE wants to issue a market power charge of 1.5 times that sum, collected monthly over a year. This kind of charge is pointed towards the larger players in New England’s power supply market: not only Mystic’s alternating owners Constellation and Exelon, but also NextEra, Iberdrola, Calpine, MMWEC, and LS Power. That last stakeholder made a mini slide deck arguing that if a resource does not cause reliability concerns, it should be allowed to drop out even faster than a two-year commitment. This is a cute pitch to an organization that will resettle market transactions over a nickel (so I thought).

If it sounds like ISO-NE wants to make closing a power plant as difficult and expensive as possible, trust your instincts. But I don’t think these reforms would have prevented the fall of Mystic or saved power purchasers the cost-service money. That plant was a genuine financial hot potato, and it was also a singularly large resource. Regardless, responses to this interim plan were grim. Buyers of power6 asked why the current structure doesn’t allow projects to back out of deactivation proceedings. Power plant owners asked, “Is this legal?” with maximum J.K. Simmons gravel. The answers, to me, seemed straightforward. ISO-NE was disallowing take-backsies because if they can’t force a power plant to stay on the market, they’ll happily make an example by crashing someone’s portfolio. And they thought the market power charge would disincentivize bad behavior.

But ISO-NE couldn’t stick to their guns. I can see why: ISO-NE does not have the buffer time to manage a legal challenge to these reforms. Even a temporary injunction would risk leaving the 2028 capacity year open. If someone really does want to challenge these deactivation reforms in court, they could kill the Capacity Auction Reforms project before a court date is set.

So ISO-NE relented. In May 2025, they walked back their plans to institute a market power charge, and they relented to LS Power’s ask for resources to back out of the capacity market even faster than two years. However, ISO-NE still wants a reliability check and market power check before approving an exit, so how quickly can a power plant leave the market, really?

Regardless, I have two takeaways from this vignette:

ISO-NE is back to the drawing board on their deactivation reforms.

ISO-NE does not have the leverage to say no to stakeholders.

No one is at the helm. ISO-NE is vulnerable. And failure here puts them at the mercy of whomever becomes President in 2029.

If you—whether you’re Alex Epstein or Bill McKibben or the DER Task Force—want to drive a knife into the Wokest RTO/ISO in the Nation, then deliver them a legal challenge in the next six months. Take ISO-NE to FERC, sink their Capacity Auction Reforms, let their backstop half-measures collapse during the next Presidential election, and point to the tattered duct tape and twine above the wreckage.

“See this? It’s not just. It’s not reasonable. Rescind FERC Order 888.”

Riding the Dragon of Tail Risk

The operative challenge of the current era, starting with early-2010s Silicon Valley and breaking containment with COVID-19, is the quantification and management of tail risk. On the upside, consider the tail risks of investing in a “unicorn” tech startup, of buying a cryptocurrency that goes to the moon, of capitalizing on AGI, of cracking fusion energy or space travel or electric vehicles. On the downside, consider the tail risks of the destruction of NordStream, of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, of Trump’s tariff decisions, of p(doom).

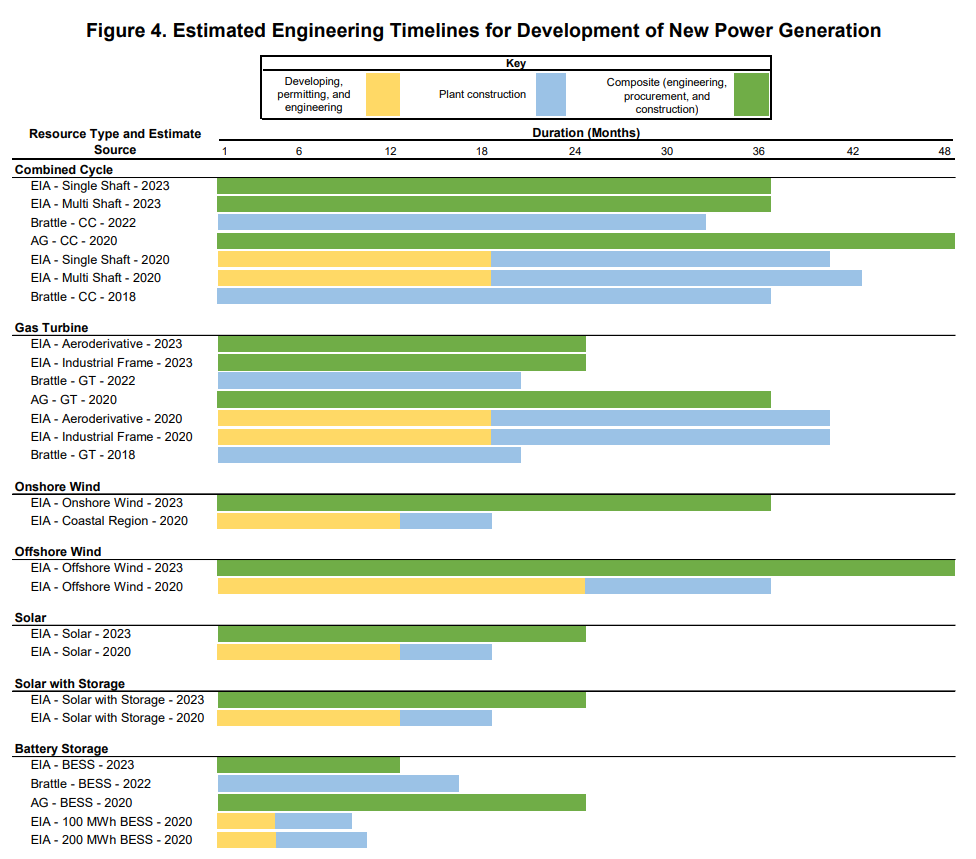

The problem with living in an era where “unprecedented” things happen on a weekly basis is that the underlying work of society still takes years. Consider these estimates of how long it takes to build power generation in the 2020s:

That’s three to four years to build a combined-cycle fossil generation system, or an offshore wind system. Imagine trying to start a project like that right now, in the Summer of 2025. Even if your project isn’t bogged down by years of legal battles, how are you going to predict your costs? Do you know what steel will cost in two years? How about copper? What tariffs will you pay on those inputs? And how much will you make on the tail end? Electricity is a commodity, too—you get very little control over your per-unit revenue. And yet you must choose, because even inaction harbors financial risk.

You are required, in 2025, to engage with these questions on every decision. My employer must make five-year cost projections knowing full well that oil and gas prices could triple tomorrow. ISO-NE must make twenty-year system projections assuming that New Englanders will keep buying electric cars. Even this blog is not exempt: I wrote my first draft of this post in April, and I had to rewrite it with new developments that broke in late May.

Notionally, homo economicus can handle a lot of that risk. Compared to the risk of AI annihilation, the expected Pay-for-Performance payouts from Capacity Scarcity Conditions are manageable on a spreadsheet. One can make stochastic high-case and low-case forecasts of how much grid capacity will cost in five years. From there, a halfway-decent regression model and a sufficiently paranoid safety factor can enable a functional hedge against the future. It won’t be perfect, but you can reach a threshold where if this hedge fails, it’ll be because you have much bigger problems.

But that requires you to have enough data to feed a model, formatted in a manner amenable to an R script, analyzed by some kid with data science chops, and managed by a real IT staff. ISO-NE is short on the analyst staff. Most utilities are short on the IT infrastructure. I suspect a lot of power plants don’t even have the data. And even if all the pieces come together, someone has to sign off on a business plan that’s hedged against edge cases less likely than a Critical Failure in Dungeons & Dragons.

Homo economicus can think stochastically. ISO-NE can operate stochastically. But what about the people bidding into ISO-NE’s markets? What if the source of capacity market inefficiencies is the grey matter of the market participants?

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only.The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of their current or previous employers or any elected officials. The author makes no recommendations toward any electric utility, regulatory body, or other organization. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, the author has not independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author assumes no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

…Although it took the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act and Russian invasion of Ukraine to motivate the rest of the industry.

You will notice that these numbers don’t match the ISO-NE report linked. This is partially because I rounded, and partially because ISO-NE likes adding “true-ups” to bills, sometimes months after the fact. As a general rule, any analysis based on ISO-NE numbers should only run off the nearest million/100k MWh or USD. ISO-NE will reach into utilities’ bank accounts for individual pennies, but they giveth and taketh away at their own discretion.

A newsletter I follow suggested another motivation for these reforms: The 2013 retirement announcement of the 1.5MW Brayton Point coal plant in Somerset, MA. Like with Mystic, ISO-NE rejected the initial shutdown proposal, leading to what seems like a legal battle that alleged that Brayton Point’s owners shut down the plant to jack up capacity auction prices in a market manipulation maneuver. The clear prices in the next Forward Capacity Auction (FCA 9) hit $9.55-$17.23/kW-month, well above Brayton Point’s rumored de-list bid price of $5-6/kW-month. The plant shut down anyway in 2018. History rhymes, etc. etc.

That is, under 10,000 residents, plus a small college campus, during a heat wave or cold snap.

Although the IMM will now review summer and winter peaks, not just summer peaks.

Typically, electric utilities